Courses: Reading Intervention, Spanish, Core Subjects Grades 9-12

Department: Special Education

Institution: Campus International High School

Number and Level of Students Involved: 56 Students with IEPs, Grades 9-12

Digital Tools/Technology: Zoom, Google Classroom, Khan Academy

Allison Welch is an Intervention Specialist at Campus International High School in Cleveland. She has a Master’s Degree from Cleveland State University and Bachelor of Arts from Hiram College. Allison has worked in many different educational settings for 12 years. She was an English teacher trainer in the Peace Corps in Nicaragua, an Educational Interpreter for Spanish-speaking students with disabilities, and an Instructional Coach before working for Campus International.

On Thursday, March 12th, Governor DeWine of Ohio announced that all schools would close due the COVID-19 pandemic. Students and teachers had one day to prepare for the temporary closure, which ended up being the rest of the school year. The Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) announced a period of learning “enrichment”, not instruction, which could take many forms. By calling this period “enrichment,” no new learning was meant to take place and the district was not responsible for any legal issues involving Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for students with disabilities. This follows the Ohio Department of Education guidance that states, “When a district or school is not in session and educational services are not provided to any student, specially designed instruction and related services are not required to be provided to students with disabilities” (2020). In doing so, the district acknowledged the many challenges students with IEPs would have in completing their work remotely without their normal learning accommodations and specially designed instructional support from their Intervention Specialists. This enrichment plan may have avoided some legal issues, but the grading practices during this time were not fair to students with disabilities, and in some cases potentially hindered their ability to graduate.

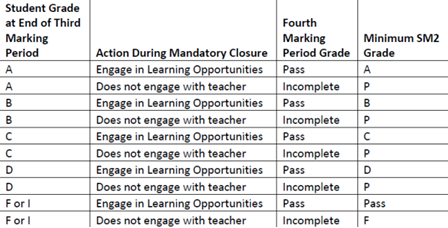

Grading during the pandemic became a debated topic in every school, school district, and online educational forum. EdSource reported, “the principle…adopted by most states, is ‘to hold students harmless’ during this pandemic. That means that the grades they receive during distance learning, will not have a negative impact on their overall GPA in relation to graduation or gaining admission to college”(2020). Some districts decided that a pass/fail or credit/no credit option would be equitable, taking into account the third quarter grades and attempts at learning. Other districts, like Los Angeles Unified School District took a “no fail” approach, deciding “None of the district’s 472,000 students will get an “F” this semester. No overall grade will drop lower than where it stood in March, when the coronavirus pandemic forced campuses to close” (Stokes, 2020). This discrepancy between letter grades and pass/fail grades can affect GPAs; possibly having college acceptance repercussions. Dr. Manuel Rustin made the argument that the only “no harm” way to grade students during a pandemic is to give them all As. He writes that giving all As, “neutralizes many complex inequities so that no student is harmed academically for being forced into this pandemic (2020). The Cleveland Metropolitan School District took a hybrid approach to grading during the pandemic. Students could not receive a grade lower than their third quarter grade for the semester, but could be bumped up with engagement in learning opportunities (see Figure A. From A. Kim El-Mallawany, personal communication, March 12, 2020). With this grading system, kids who had failing grades in the third quarter were in danger of losing credit for the entire semester if they did not show “engagement.” This system became especially problematic for the kids with disabilities who were failing third quarter and needed to show engagement to receive credit for their classes.

“Enrichment” was not clearly defined by the district or understood by the teachers, so without a unified understanding, individual teachers used their own discretion to grade students. The district sent home multi-page paper/pencil learning “packets,” but allowed individual schools to create and utilize their own online resources. These “packets” came with instructions for students and parents on how to differentiate lessons at home for some disabilities. Campus International High School was ahead of the curve, and created a schedule of online learning quickly. Students who had the technological access and time, logged into Google Classroom, Khan Academy, and other online learning platforms their teachers set up, and received the support of teachers through Zoom meetings. While these efforts were commendable, parents, students, and Intervention Specialists, were left with unclear expectations as to which “enrichment activities” would count for grades and graduation credits. As for the “packets”, there were no guidelines for turning them in to teachers for credit other than doing it digitally, which was a huge headache for parents who were not tech-savvy. Teachers gave no expectations as to how much of the packet was considered enough for a passing grade.

Grading guidelines led to unfair practices, and did not take the regular progression of the school year into consideration. The shutdown began just after the end of the third quarter, when interim grades were issued. Interim grades are usually non-credit-bearing grades; meaning students still have time to improve their grades and earn a semester-worth of graduation credits. In a normal school year, Intervention Specialists would make a list of students with failing or close-to-failing grades, and double up our efforts with those students to improve their grades to passing by the end of the year. During the shutdown, the district decided that the third quarter grade was now the final grade for the semester, but gave students the opportunity to improve their grades by engaging in the broadly defined “enrichment”. This left students who received good grades “off the hook” for completing enrichment work, while students who failed a class had to show “enrichment” by completing the differing expectations of their teachers. Typical students with failing grades had difficulties completing the expectations, let alone students who were accustomed to having the support of an IEP and Intervention Specialist to complete their work. Students with disabilities did not have the same opportunities as their typically abled peers to improve their grades, affecting some students negatively in their grade point averages and graduation credits.

Intervention Specialists and parents did their best to help students engage in learning during the pandemic, but inequity abounded anyway due to a range of obstacles. Campus International High School had 56 students enrolled IEPs (about 30% of the total population) under a range of nine disability categories (out of 13): Autism, Blindness, Emotional Disturbance, Hearing Impairment, Intellectual Disability, Other Health Impaired, Specific Learning Disability, Speech or Language Impairment and Visual Impairment. Implementing the accommodations and modifications of this range to every student remotely, was close to impossible for four Intervention Specialists. To begin, we were not even able to contact several of the students, so that alone was a challenge. Many of the disabilities involve difficulty with executive functioning skills; including planning, self-control, memory, following directions, and handling emotions. Without the structure, routine, and support built into a typical school day, many kids could not engage in learning. Students called teachers for help in the middle of the night, or sleep right through planned help sessions. Some kids had significant language and reading delays, making even the directions of online tasks impossible for them. Many accommodations include reduced complexity of tasks, meaning multi-step tasks, (anything involving technology) were too challenging. Even the learning “packet” was inaccessible for a student who needed enlarged text to read. Intervention Specialists posted office hours, scheduled individual online meetings, checked online platforms, sent emails, made phone calls, and even engaged through social media, but the best efforts did not reach every student when they needed help. It was not the fault of the students, parents, teachers, or Intervention Specialists that needs were not met, it was just the nature of the unplanned shutdown. Kids with disabilities should not be held back in grades and credits because of a situation nobody had control of.

Given these difficulties, and the general difficulties of living through the disruption of a pandemic, it makes sense to take a “no harm” approach to grading, while encouraging any learning that students are able to do. The best way to make this equitable is to make sure at the very least, every student receives graduation credit. In the words of a highly esteemed colleague, Charles Ellenbogen, “Any attempt to punish a student for failing to complete work or failing to submit their best work while we’ve been in quarantine is just that – a punishment. A reminder (as if they need it) about who has power and who does not.” We must give students the benefit of the doubt that they would have at least improved their grade to passing had they been in school. Students with disabilities had no preparation and received varying levels of their typical support, so at the very least they should not fail a course. There is no way for any teacher to know which students would have improved in the last quarter under normal circumstances. Since some districts continued with letter grades, while others went to pass/fail, hopefully college admissions will acknowledge that GPAs will be more inequitable than they typically are. It would do the least harm if every student received an A. We are all learning how to manage a pandemic, and everyone deserves credit for that.

Bibliography

Edsource Staff. (2020, April 22). Quick Guide: Grading K-12 Students During a Pandemic. Edsource. https://edsource.org/2020/grading-k-12-students-during-a-pandemic-an-edsource-quick-guide/629535

Ellenbogen, Charles. (2020, May 19). An Open Letter to My Colleagues Around the World. After25YearsBlog. https://edsource.org/2020/grading-k-12-students-during-a-pandemic-an-edsource-quick-guide/629535

Gavin, Jennifer. (2020, March 31). Are Special Education Services Required in the Times of COVID-19? American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/childrens-rights/articles/2020/are-special-education-services-required-in-the-time-of-covid19/

Goldstein, Dana (2020, April 30). Should the Virus Mean Straight A’s for Everyone? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/30/us/coronavirus-high-school-grades.html

Ohio Department of Education. (2020, March 17). Students with Disabilities: Considerations for Students with Disabilities During Ohio’s Ordered School Building Closure. ODE. http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Student-Supports/Coronavirus/Considerations-for-Students-with-Disabilities-Duri

Rustin, Manuel. (2020, March 31). Give Them All A’s. Medium. https://medium.com/@manuelrustin/give-them-all-as-7ea4d0cc52ba

Sawchuck, Stephen. (2020, April 1). Grading Students During the Coronavirus Crisis: What’s the Right Call? Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/04/01/grading-students-during-the-coronavirus-crisis-whats.html

Stokes, Kyle. (2020, April 27). No Right Answers: How Schools are Grading Students During the Coronavirus. LAist. https://laist.com/2020/04/27/coronavirus_school_grades_no_fail_grading_credit_lausd.php