Courses: SOC 201: Race, Class, and Gender; SOC 353: Methods of Social Research

Department: Criminology, Anthropology, and Sociology

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Marnie S. Rodriguez

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: Race, Class, and Gender had 150 students in two sections of 75, 200-level general education course; Methods of Social Research was one class of 22 students; 300-level required course

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Blackboard Learn, Panopto Video, PowerPoint, Zoom

Author Bio: Marnie Rodriguez is a Senior College Lecturer at Cleveland State University. She teaches a variety of courses in Sociology, ranging from introductory-level general education courses to upper-division electives and required courses.

Rationale for Remote Learning Delivery Decisions

Three goals guided my decisions when moving to remote learning. These goals were to (1) keep the course requirements as similar to the original as possible, (2) make the delivery of course materials flexible for students whose schedules may have changed due to the pandemic, and (3) encourage students to engage with the course materials each week in order to keep their learning on track.

I incorporated principles from professional development opportunities at CSU on Small Teaching (Lang 2016), Flipped Learning (Talbert 2017), and best practices for online teaching (Boettcher 2019, Johnson 2013). For instance, I gave students the ability to make connections to the material and to practice what they learned (Lang 2016). Additionally, I let students be responsible for achieving basic learning objectives on their own but to also work collaboratively to achieve higher-order learning objectives (Talbert 2017). Finally, I communicated expectations to students and provided feedback to a large number of students effectively (Johnson 2013).

In this essay I will address Blackboard online discussion board assignments in two sociology courses. Race, Class, and Gender is an introductory level general education course. This course is lecture-based with guided discussions and a few small group activities. The course enrolled 150 students divided across two sections in Spring 2020. Methods of Social Research is an upper-level required course for both the sociology and criminology majors. I typically deliver this course with short lectures and class activities. In Spring 2020, 22 students were enrolled.

Discussion Assignments in a Large General Education Course

I added two asynchronous Blackboard group discussion board assignments in Race, Class, and Gender when the course went remote. The goal of both of these assignments was to cover material that we would have addressed in a class discussion, to encourage students to engage with the weekly learning materials, and to replace the class-participation points associated with attending lectures and participating with a clicker device.

For each discussion board assignment, students were required to read material or view a short video lecture that I recorded and then to respond to a prompt. I gave students some flexibility on the questions they responded to because giving students choices can enhance their learning (Boettcher 2019). Giving choices benefits students because it allows them to make connections between their own experiences and what they are learning (Lang 2016).

In one of the discussion assignments, students evaluated a selection of scenarios provided by the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (2006, 2008) to test their knowledge of anti-discrimination policies discussed in the lecture. Although all students were required to address one of the given scenarios, they had a choice in selecting a second one to discuss. By applying information learned in lecture to the scenarios, they had to retrieve knowledge and practice using it which should help them retain the information (Lang 2016).

Given the number of students in these sections (150 total), I graded on a very simple rubric. Students who addressed the initial post and responded to classmates by the required deadlines earned full credit. If they submitted part of the assignment late, they earned half credit on that portion of the rubric, and if they did not complete a requirement, they earned no credit for that part of the assignment. Utilizing rubrics and giving limited personalized feedback are strategies that can reduce faculty workload while still providing feedback to improve student learning (Johnson 2013; U of MN Academic Technology Support Services 2016).

Lessons Learned in Race, Class, and Gender Discussions

Grading and Feedback. Evaluating discussion boards can be quite time-consuming. Utilizing rubrics helped make the process of assigning points easier. Additionally, for one discussion I wrote a follow-up post that summarized the most common student responses, indicated whether or not each scenario violated anti-discrimination policies, and explained why or why not. This took much less energy than giving individualized feedback to each student. I posted this feedback as an announcement on Blackboard and sent it in an e-mail to maximize the chances that a student would see it.

Group Number/Size. Creating fewer groups was more manageable. I initially kept students in the same 4-person groups that the students had been working with throughout the semester before going remote. This proved to be unwieldy in the remote setting because I had to create the prompts, assign due dates/point values, and add rubrics to 38 different discussion groups on Blackboard. Not only was it time consuming, but I made a few errors in the process. For the second assignment, I only created 5 groups per section which was much more manageable. I also think having 15 students per group benefited students more because they could learn from a variety of comments from their peers.

Participation. The number of students who submitted the discussion assignments in the remote setting was about the same or a little higher than the number of students who typically participated with a clicker in class. One of the strengths of these assignments is that more students engaged in the “conversation” than would typically in class. I usually ask students in class to think about these prompts before we discuss them as a group, but I only get to hear from those that are willing to raise their hand. In the online discussion environment, I could see that students who refrain from speaking in class were engaged with the material.

Discussion Assignments in an Upper Division Required Course

In Methods of Social Research, I applied principles of “flipped learning” (Talbert 2017) to the discussion assignment after the course went remote. With this pedagogy, students are expected to accomplish the basic learning objectives by engaging with learning materials on their own. Then, students work together (most often during class time) to gain mastery of more complex learning objectives involving higher order thinking. The instructor typically assists students during the group work sessions. I incorporated flipped learning in the following online discussion.

I assigned a textbook chapter and two short video lectures that I created using Panopto. Students were also required to read parts of a journal article that utilized experimental and survey methods (Willer, Conlon, Rogalin, Wojnowicz 2013) and to answer some basic questions about this article (e.g. What are the hypotheses? What is the experimental group?). These questions assessed students’ understanding of the basic (i.e. least complex) learning objectives for the week.

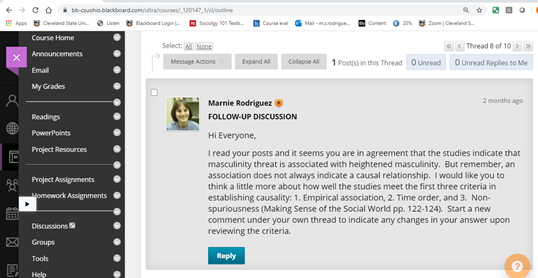

To help students gain a deeper understanding of the material, I asked them to evaluate how well the studies they read in the journal article established causality and to share their thoughts in an initial discussion post. They were also responsible for reading their classmates’ posts and commenting on at least two by a second deadline. The goal was for students to work together to apply their knowledge and generate a deeper understanding of the criteria for establishing causal relationships in research.

I gave students feedback throughout the discussion by posing questions or giving short affirmative comments. After the deadline, I provided a detailed thread to explain the strengths/weaknesses of the common responses and provide a solution to the prompt. Students earned full credit if they completed the initial post and responses by the deadlines. Students were challenged to apply the materials, to self-correct, and to work together to solve a problem in this assignment which should foster deeper learning.

Lessons Learned in Methods of Social Research Discussions

Keeping the Discussion On Track. I found it more challenging to direct the online discussion back to the learning objectives compared to facilitating an in-person discussion. Several students commented on things that we covered earlier in the semester as opposed to focusing on the learning objective for the assignment. Had this discussion taken place face-to-face, I could have quickly shifted the discussion back by reminding students of the question at hand. In the online discussion, it wasn’t as simple because students are not a captive audience for the duration of the discussion period. To attempt to shift the discussion, I posted a follow-up thread that reminded students about the criteria that they learned in the reading/lecture and asked students to evaluate the studies using these criteria and to post a response in their own thread.

Continued Participation. In a flipped learning environment, the group work takes place in the classroom with assistance from the instructor (Talbert 2017). Therefore, I tried to assist students’ learning by inserting questions into the discussion to get them to reflect on their answers and to self-correct. However, some students didn’t respond to questions/feedback and may not have even read them. In fact, about 1/3 of the students who participated in the initial discussion did not engage in the follow-up. This is due to the asynchronous nature of the assignment; once students completed the initial post and required number of responses, they may have ‘put the assignment away’ so-to-speak. If I were to do this kind of an assignment in the future, I might include three deadlines, one for the initial posts, one for the initial feedback, and one for following-up on comments/questions. Each of these parts of the discussion would also be included on the rubric.

Conclusions

Online discussions can be used to encourage students to engage with the course materials, practice what they learned in the readings/lectures, and gain a deeper understanding of the course objectives. Limiting the number of groups, providing group-level feedback, and using grading rubrics can help to keep the workload manageable for faculty while still providing effective feedback for students. The biggest challenge that I faced was non-participation or initial participation with no responses to follow-up questions. However, this weakness is offset by the fact that far more students participated in the conversation, overall, than would have in the face-to-face environment.

References

Boettcher, J.V. 2019. “Ten Best Practices for Teaching Online.” Designing for Learning. Retrieved June 1, 2020 (http://designingforlearning.info/writing/ten-best-practices-for-teaching-online/)

Johnson, Aaron. 2013. Excellent! Online Teaching: Effective Strategies for a Successful Semester Online. Self-published.

Lang, James M. 2016. Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Talbert, Robert. 2017. Flipped Learning: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

U of MN Academic Technology Support Services. 2016. “Planning and Facilitating Online Discussions.” You-Tube Website. Retrieved June 1, 2020. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sOkxbw1TzNk&feature=youtu.be)

U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. 2008. “Section 12: Religious Discrimination.” Retrieved June 1, 2020 (https://www.eeoc.gov/laws/guidance/section-12-religious-discrimination)

U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. 2006. “Section 15: Race and Color Discrimination.” Retrieved June 1, 2020 Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org/web/20150208042559/http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/race-color.html)

Willer, Robb, Rogalin, Christabel L., Conlon, Bridget, and Wojnowicz, Michael T. 2013. “Overdoing Gender: A Test of the Masculine Overcompensation Thesis.” American Journal of Sociology. 118(4): 980-1022. https://doi.org/10.1086/668417