Course: SWK 694 Theories and Procedures in Addiction Studies, HSC 625 Interprofessional Healthcare Teams Seminar II

Department: Social Work, Occupational Therapy, Physical Therapy, Nursing, Speech Therapy

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Patricia Stoddard Dare, Kelle DeBoth, Madalynn Wendland, Cyndi Hovland

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: PowerPoint, Blackboard, email, YouTube, Zoom

Author Bio: Patricia Stoddard Dare, MSW, PhD is a Professor in the School of Social Work and Coordinator of the Chemical Dependency Counseling Certificate Program at Cleveland State University. She completed her graduate work at the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis. She is a co-Director of the CSU T.E.C.H. Hub.

Kelle DeBoth, PhD, OTR/L is an Assistant Professor in the Occupational Therapy program at Cleveland State University. She completed her doctoral work at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, VA and is Co-Academic Director for the Internet of Things Collaborative.

Madalynn Wendland, PT, DPT is an Associate Clinical Professor in the Doctor of Physical Therapy Program in the School of Health Sciences at Cleveland State University. She received her education at The Ohio State University and University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

Cyndi Hovland, Ph.D., MSSW is an Associate Professor and MSW Program Coordinator in the School of Social Work at Cleveland State University. She completed her graduate work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Introduction

Cleveland State University has spent time over the last five years developing infrastructure to support interprofessional education. Required by external accreditors, interprofessional education (IPE) refers to opportunities where health professionals “…learn about, from and with each other” (WHO, 2010) to develop skills that align with interprofessional collaborative care that best supports the patient being served. IPE teams now benefit from established professional relationships where we have supported each other’s teaching, service, and scholarship.

One past successful educational event that was designed to support and foster interprofessional education focused on nonpharmacological approaches to patient pain to address the opioid epidemic. Specifically, this event was designed so students learn the roles and responsibilities of nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and speech therapists as they pertain to patients experiencing pain or who are at risk for substance use disorders. Importantly, this educational event features time for interprofessional work where at least one student representing each profession comprises an interprofessional team.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, an in-person spring 2020 event was initially postponed; then, later, it was reimagined to take place as a synchronous interactive virtual event in the fall of 2021. This case study will share the authors’ experiences designing this IPE event for a virtual platform. The value of this event has increased as fatal drug overdose has substantially increased over the last two years (Cuyahoga County Overdose Fatality Review, 2020; DeBoth, Bruce, Stoddard-Dare, & Wendland, 2020; Stoddard-Dare, DeBoth, Wendland, Suder, Niederriter, Bowen, Dugan, & Tedor, 2020). We will offer details on the specific decisions we made about the structure and design of the event as well as some of our reflections and recommendations for practitioners interested in organizing and planning similar events.

Structure of the event

- The Zoom event started with a brief welcome from event organizers.

- Next, a person in long-term recovery shared her experience of working with medical professionals during the time in her life she struggled with pain and opioid dependence.

- Following, an expert shared about nonpharmacological approaches to pain management.

- Then, professors from social work, nursing, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech therapy spoke very briefly about their profession’s role pertaining to substance use disorders and pain management.

- After this, a case study of a young pregnant mother currently using heroin was introduced.

- Students were then moved into breakout rooms for discipline specific “professional huddles,” where, for example, all social work students met together to briefly discuss how their profession might approach the patient from the case study.

- Students were then brought back into the main Zoom room to learn about a local treatment and harm reduction finder tool called drughelp.care.

- Then, breakout rooms were used to allow different pre-assigned interprofessional teams to “meet,” The composition of these teams were intentionally designed to include at least one student from each profession. The students reviewed the role of each profession pertaining to the case study.

- The event ended with students returning to the main Zoom room for a wrap up and debriefing.

The event itinerary:

- Welcome (1:00-1:05pm)

- Guest Speaker, community advocate with lived experience in long term- recovery (1:05-1:25pm)

- Guest Speaker, non-pharmacological pain management specialist (1:25-1:45pm)

- Interprofessional response to pain and the opioid epidemic (1:45-2:00pm)

- Introduction of the case (2:00-2:05pm)

- Professional huddle (2:05-2:15pm)

- Introduction of drughelp.care (2:15-2:25pm)

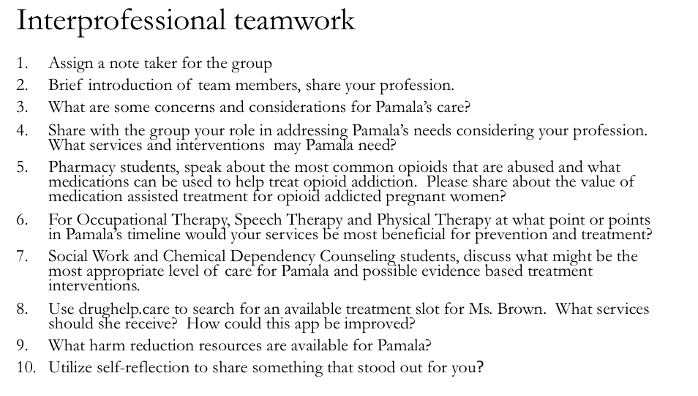

- Interprofessional Teamwork (2:25-2:50pm)

- Debriefing and wrap-up (2:50-3:00pm)

The logistics of organizing a large interactive event

Detailed planning is required to implement a large interprofessional event that includes students from multiple classes and multiple breakout rooms.

Step 1: recruiting professors and classes for participation

In the spring of 2021, a planning meeting was held to discuss fall 2021 IPE events. During that meeting, it was determined we wanted to host an interprofessional event focused on opioid prevention and intervention in the fall of 2021. During the summer of 2021 various elements had to be arranged before the event was finalized.

Step 2: Finding a date and time that works for all participating students

The various classes that were slated for participation follow vastly different schedules. For example, Occupational Therapy students have classes scheduled in person during the weekday; whereas the Master of Social Work program has a fully online asynchronous option for students who work full time. A master calendar was sent to all participating programs to rule out certain dates such as when national, state-wide, or local annual conferences take place. The dates of other IPE events were also taken into consideration. Ideally, this event would take place near the middle to end portion of the semester so that students would be more fully oriented to their profession; however, due to scheduling constraints, this was not possible. In the end, all agreed to an event that would take place on a Friday afternoon during the third week of class.

Step 3: Arranging keynote speakers

Arranging keynote speakers for an online event is much easier than arranging speakers for an in-person event. In this case, we invited our speakers to either speak live or to pre-record their speech. One speaker chose to speak live. The other speakers chose to pre-record her presentation and sent us the YouTube link. In addition to the benefit of allowing us to secure a high demand speaker that would not have been available to present synchronously during our event due to schedule constraints, having a guest speaker pre-record her remarks also helped with time management because the organizers knew exactly how long the speech would last, and were not put in the awkward position of having to interrupt a speaker in order to stay on schedule.

Step 4: Sharing event details with participating professors

To ensure adequate participation, it was important that the basic details of the event such as the date, time, and draft of the itinerary were shared with professors whose students would be participating in this event early enough so that the professors could adjust their fall 2021 syllabus before the start of the semester. Each professor was free to make their own determination if a graded assignment would be attached to this event, or if event attendance would be graded for their specific course.

Step 5: A list of participants

Initially, professors sent an estimate of the number of students that would be participating from each discipline to the event organizers. This estimated count was important because it helped the event organizers determine how many facilitators would be needed for the event. The initial estimate was 200 students from five or six disciplines. We have partnered in the past with a local external university that has sent students from two additional disciplines. Part of successfully executing this type of event is functioning with a high degree of flexibility and understanding that collaborating disciplines may need to operate on a different schedule to confirm their participation. It may be only days before an event when the final list of participants is known. We allow space for this. Approximately a week before the event, a final list of participants’ names and email addresses was solicited from each professor and emailed to the event organizers.

Step 6: Forming interprofessional teams

A key educational component of this event is having students participate in an interprofessional team. Each interprofessional team consists of at least one student from social work, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech therapy. For this event, there were a total of 16 interprofessional teams with approximately ten students per team. Professors flagged students who had demonstrated poor attendance so they would not be the only individual representing their profession on a team.

Step 7: Facilitators

Professors sending students to the event were asked to serve as breakout room facilitators during the interdisciplinary team portion of this event. Additionally, graduate assistants and teaching assistants were invited to serve as facilitators, and other professors from the programs represented volunteered. The full list of facilitators was not settled until a few days before the event. Facilitators were invited to attend a brief online facilitator training via Zoom the morning of the event.

Strategies for featuring multiple speakers, and moving students to multiple purposeful breakout groups first by profession, and then with group members equally representing each of the various participating health professions.

Methodically plan the movement of students during this event

As described above, this event required students to first spend time together in the main Zoom room. Then, students needed to be moved into discipline-specific breakout rooms called “professional huddles.” Then, we wanted to move students into interdisciplinary teams with at least one student per discipline represented on each team. In other words, we needed to move each student multiple times during the event into different teams. To do this required planning.

Create and circulate a spreadsheet

We started by creating a spreadsheet with the name, discipline, and email address of each student. Students were then pre-assigned to an interprofessional team numbered one to sixteen, and a Zoom room facilitator was assigned to each team to help keep the interprofessional team on track while in the breakout room.

Pre-event email to students

Days before the event, the spreadsheet was emailed to all participants. Students were asked to bring to the event their interprofessional team number. Students were also emailed the event itinerary, a description of the case study, and a copy of the reflection questions students would work through while in their interprofessional team during the event

Pre-event email to presenters, professors and facilitators

In all, the event included a speaking role for

- two event organizers who served as conveners of the event,

- two keynote speakers,

- five professors who spoke about their disciplines,

- another guest speaker who spoke about drughelp.care, and

- 16 facilitators who were tasked with encouraging all students to participate in their breakout rooms.

The same content that was emailed to the students was also emailed to the presenters, professors, and facilitators. Additionally, the presenters, professors, and facilitators were also sent a copy of the PowerPoint that would be used throughout the event and a detailed description of who was responsible for speaking during each minute of the event.

External helper

We perceived a need to have a professional with expertise in convening large online events to help manage the movement of students into the various breakout rooms. Days before the event, the event planners met with this individual to describe the precise needs of moving students into the various breakout rooms. The detailed plan was communicated in writing and was discussed verbally.

The important role of the Zoom name

A critical component of this program is being able to quickly move participants into different Zoom breakout rooms. We utilized a strategy that made this process more user-friendly. Upon arrival to the Zoom event, all participants were instructed to use the “rename” function in Zoom to name themselves using the following formula: interprofessional group number, first and last name, acronym representing their profession (SWK, OT, PT, SPL).

For example, “13, Patricia Dare, SWK” or “11, Kelle DeBoth, OT.” This allowed the external helper to quickly identify which participants needed to be moved into which breakout room. For example, the first breakout room was the “professional huddle” so all SWK were placed together, all OT were placed together, all PT were placed together, and all SPL were placed together. We had originally planned to move students directly from the professional huddle to the interprofessional teams but we realized that the external helper needed more time to reconfigure the breakout room composition. As a remedy, we rearranged the schedule and had the students move from the main zoom room > to the professional huddle breakout room > back to the main Zoom room for ten minutes > to the interprofessional breakout room. There were 16 interprofessional breakout rooms and it was easy to quickly move students to the appropriate breakout room based on their Zoom name code. The spreadsheet that was created and sent out before the event provided everyone with easy access to the participant’s profession and interprofessional team number.

Recommended changes to the timing and format of the event

Based on our experience we would recommend some changes if we implement this program again virtually in the future.

- Extend the total amount of time allotted for the event from two hours to three hours, which will include a short break in the middle.

- Schedule more time at the beginning (perhaps ten minutes) to assist students who are having technical challenges as they access the meeting.

- Use Microsoft Teams to create and share documents.

- Prepare to quickly place in the chat each individual’s name and group number. We only had this information available in Excel format, and it would not copy over quickly into the Zoom chat. We need to expect that some students will need a reminder.

- Create and circulate a shared document event checklist which clarifies who is tasked with each responsibility and check off when each item is complete.

- Be prepared to push out a copy of the case study and the case study questions to each interprofessional teams in each breakout room.

- Consider pre-recording professor’s comments about the role of each profession in pain and substance use disorder prevention.

- Enable the automatic record function in Zoom so the event can be shared with students who were not able to attend.

Works Cited

- Cuyahoga County Overdose Fatality Review Annual Report, 2020 released March 2021 https://www.ccbh.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/OFR-Annual-Report-2020.pdf

- DeBoth K, Bruce S, Stoddard-Dare P, & Wendland M. (2020). The Opioid Epidemic: An Interprofessional Response to Pain. “Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice: International Approaches at Micro, Meso and Macro Practice Levels.” Joosten-Hagye. San Diego, CA: Cognella Academic Publishing. In press.

- Stoddard-Dare, P. DeBoth, K., Wendland, M., Suder, R., Niederriter, J., Bowen, R., Dugan, S., & Tedor, M. (2020). An interprofessional learning opportunity regarding pain and the opioid epidemic. Advances in Social Work Practice, 20(2). DOI:10.18060/23656.

- DeBoth, K., Stoddard-Dare, P., Bruce, S., & Niederriter, J. (2019). An interprofessional case study competition addressing community healthcare needs and the opioid crisis, Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 15, 114-118. DOI: 10.1016/j.xjep.2019.03.007

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/index.html.

We would like to dedicate this case study to our beloved colleague Dr. Ryan Suder who devoted his career to reducing patient pain and continued to support our interprofessional efforts as he bravely fought a glioblastoma