Our society, between early 2020 and the present, has experienced a harrowing, global pandemic, horrifying brutalities committed against BIPOC individuals and communities, uprisings for racial justice, and a violent attack on our nation’s Capital. While these events and phenomena have been incredibly challenging and traumatic, they have also inspired dialogue and calls for action. It is critical that educators (at K-12 and higher education levels) have the competencies to support their students in understanding these issues through accessing accurate information, appreciating history, facilitating productive dialogues, and developing social justice literacy. As a teacher educator at the undergraduate and graduate level, I focus on developing my students’ (future teachers) social justice literacy in a variety of ways. Developing social justice literacy has long been a core focus of my teaching, yet the move to exclusively remote instruction required that I reconsider some of my instructional approaches and figure out ways to foster collaborative, critical thinking in virtual spaces.

One text I use across the various courses that I teach is Sensoy & DiAngelo’s (2017) Is Everyone Really Equal? An explicit purpose of this text is to nurture students’ social justice literacy. The authors of the text emphasize that social justice literacy encompasses both understanding and action. A person engaged in critical social justice practice must be able to:

“Recognize that relations of unequal social power are constantly being enacted at both the micro (individual) and macro (structural) levels.

Understand our own positions within these relations of unequal power

Think critically about knowledge; what we know and how we know it.

Act on all of the above in service of a more socially just society” (p. xx – xxi).

Sensoy & DiAngelo’s (2017) Is Everyone Really Equal?

Throughout this essay, I will describe how I try to support students in each of these abilities through remote instruction. Throughout the past year, my remote instruction has involved asynchronous and synchronous activities. My students often learn fundamental material asynchronously, through independently reading, watching video lectures that I create, and engaging with media resources I link to such as films, podcasts, etc. I use synchronous class time (typically, no more than two hours per meeting) for collaborative learning, where I often ask my students to apply the content they have learned asynchronously to new or more complex material. It is in these synchronous activities that I create learning experiences that allow students to practice exercising their social justice literacy.

Recognize that relations of unequal social power are constantly being enacted at both the micro (individual) and macro (structural) levels.

In order to support students’ recognition of unequal power dynamics, I engage students in reading texts which, in accessible language, describe such dynamics. Texts I use besides Sensoy & DiAngelo’s (2017) are Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty by Paul Gorski (2018) and We Want to Do More Than Survive by Bettina Love (2019) (shown in Figure 1). These texts give students the ability to understand inequities in societal power dynamics and how those dynamics are constantly enacted at the individual and structural levels.

Course Texts that Support Student Understandings of Relations of Unequal Social Power.

In order to contextualize important, sensitive, and critical topics (such as white supremacy, racism, violence, and inequity), I link contemporary events and dynamics to historical ones. This can help students to process how these events and dynamics are structural and systemic. I expose students to popular historical works like Richard Rothstein’s (2017) The Color of Law and Isabel Wilkerson’s (2011) The Warmth of Other Suns, and works with a local focus such as Charlise Lyle’s (1994) Do I Dare Disturb the Universe? and Leonard Nathanial Moore’s (2002) “The School Desegregation Crisis of Cleveland, Ohio, 1963 – 1964.” Especially for students who have experienced less socialization and scaffolding at home related to understanding race and racism, these texts help to illuminate how systems of power have worked historically, and support students in seeing how such systems shape society today.

Course Texts that Illuminate History for Students

Understand our own positions within these relations of unequal power.

The readings that we do in class serve as entry points for discussions that examine unequal relations of power in society and our positions within those relations. I often assign “educational autobiography” assignments, where students are required to reflect on how their identities (race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, gender, sexuality, ability status, etc.) and the contexts in which they grew up shaped their educational experiences and trajectories (see Appendix A for sample assignment guidelines). This often clarifies for students how power dynamics privileged or marginalized them, in various and intersecting ways.

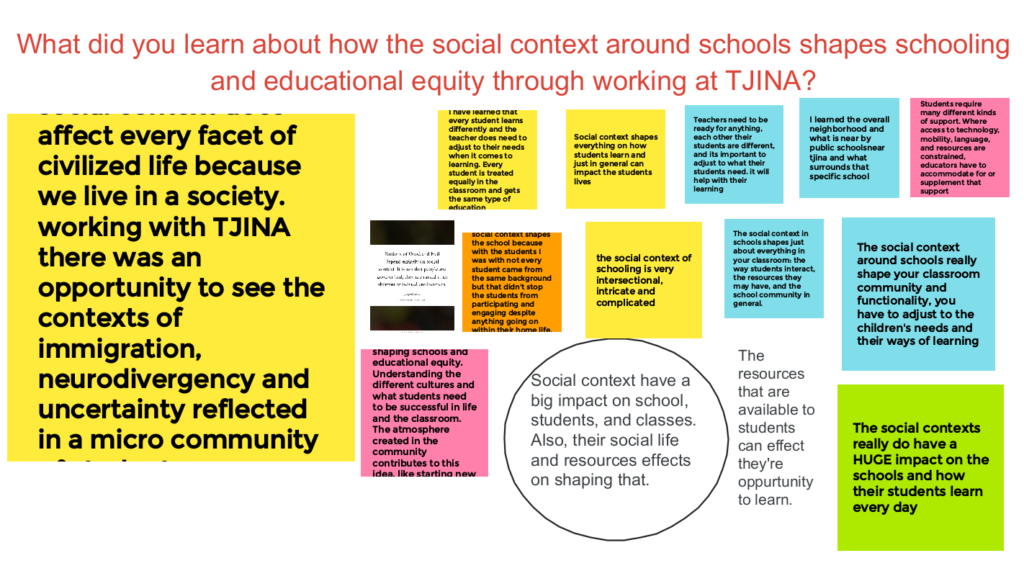

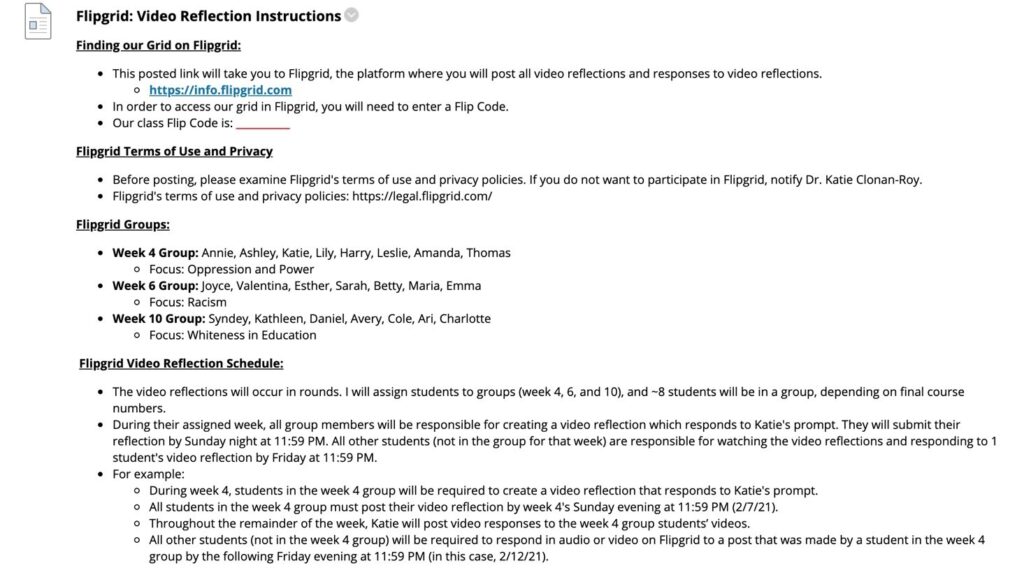

While we strive to make as much time for collaborative discussion and analysis in class, we do not always have time to complete our discussions. So, I assign reflective assignments on the platform Flipgrid, where students are required to examine readings in relation to their lives, and learn through comparing and contrasting their experiences with others. Students complete Flipgrid reflections in “rounds”. I will offer an example of how I structure these “rounds” for a class of 25 students. In week 2 of the semester, students A, B, C, D, and E, respond to a question I have posed regarding the readings with a video reflection (5 minutes or less). The 20 other students are required to respond to one student who has posted (A, B, C, D, or E). All students are evaluated using a rubric, with a requirement to cite the readings that we are examining. In week 3 of the semester, students F, G, H, I, and J post a video reflection in response to a question I have posed, and then the 20 other students respond to one of those students (F, G, H, I, and J). These rounds continue throughout the semester (see Appendices B and C for the guidelines and rubric, respectively, that I offer through our learning management system, Blackboard). This online space gives students the option to reflect upon complex ideas, to connect those ideas to their own experiences, and to engage in conversation with others.

Think critically about knowledge; what we know and how we know it.

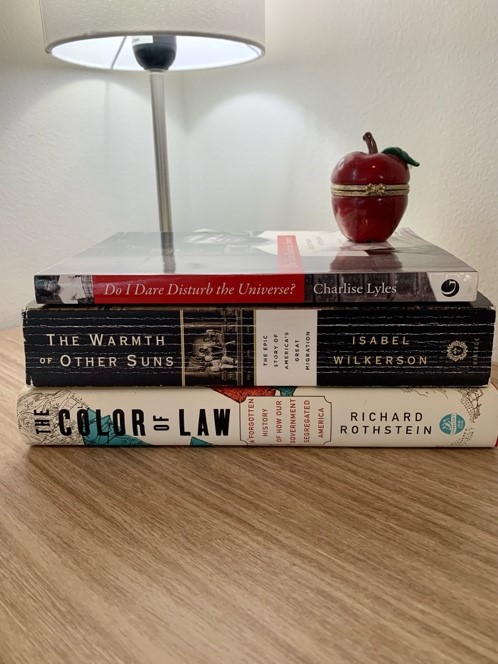

Sensoy and DiAngelo’s (2017) text explicitly instructs students to decipher between opinion and informed knowledge and to determine what is anecdotal evidence versus peer-reviewed research. The activities in my classes are grounded in examining local data to better understand the communities, students, and families we serve, without making assumptions. We use online resources to do research, such as the Center for Community Solutions’ Community Fact Sheets, Healthy Cleveland’s HEAL Maps, and Ohio School Report Card data. Using Zoom breakout room features, students will look at specific pieces of local data and be tasked with connecting that local data to our class readings. After breakout room time, all students come back to the main Zoom room to share what their small groups discussed. To make things clear for all learners and learning styles, I often ask students to not just talk about their findings and analysis, but to present visuals, by using software like Canva, Google Jamboard, or Padlet. In Figure 3, for instance, students reflected on what they had learned about the social context of education, by jotting down quick thoughts on a Jamboard. When I called on students to elaborate on their sticky notes on the Jamboard, I asked them to call upon local evidence (using the Fact Sheets, Heal Maps, or Report Card data) to support their assertions. In learning experiences like this, I make to emphasize the importance of supporting interpretations with data, rather than making leaps or assumptions.

A Jamboard about the Social Context of Education

Act on all of the above in service of a more socially just society.

Throughout the courses that I teach, we always come back to the question, “now what?” For example, now that students have learned about racial and economic segregation in Cleveland’s communities and schools, what do they do about it? In such an instance, we brainstorm what they could do about it in their classrooms or future classrooms and how this knowledge can shape their advocacy, activism, and decisions as voters. In written papers, I often ask students to conclude by offering recommendations for addressing social inequities through pedagogy and out-of-school advocacy efforts. In undergraduate courses that I teach, I ask students to apply what they have learned about critical pedagogies and societal inequities to their lesson plans and teaching demos. These training activities support my students in their development as future educators who are able to exercise social justice literacy.

Appendix A

Educational Autobiography Assignment

Assignment Purpose and Description:

- Your first assignment in this course is to compose a reflective, educational autobiography, related to course themes.

- In this educational autobiography, you will reflect on the following three questions:

- How were your educational experiences shaped by race, ethnicity, immigration status, class, gender, sexuality, ability status, your community context, and/ or other social identity factors?

- How did or didn’t you learn about the myth of meritocracy in your developmental or educational experiences?

- Using the course readings from week 2, how do you think the history of American education shaped your educational experiences?

Specific Instructions:

- Due date: Sunday, 1/31/21 at 11:59 PM

- Required length: Approximately 3-5 pages.

Citation requirements:

- In response to question 1, you must demonstrate an understanding of the theory of intersectionality.

- In response to questions two and three, you must cite one course reading in each of your responses.

- You need to include parenthetical/ in-text citations, but you do not need to provide a reference list.

- Format:

- Complete your autobiography in the template that is provided below. When you have completed the assignment, save this document using your last name, and turn the assignment in on Blackboard.

- Reflective guidelines:

- Choose personal/ educational experiences that you are comfortable telling your instructor (Dr. Clonan-Roy) about. How revealing the autobiography ends up being is totally under your control.

- The events that you choose to write about should pertain to your K-12 experiences in education.

| Questions | Autobiographical Reflections |

| Question 1: How were your educational experiences shaped by race, ethnicity, immigration status, class, gender, sexuality, ability status, your community context, and/ or other social identity factors? In answering this question, you must demonstrate an understanding of the theory of intersectionality. | |

| Question 2: How did or didn’t you learn about the myth of meritocracy in your developmental or educational experiences? In answering this question, you must cite one course reading. | |

| Question 3: Using the course readings from week 2, how do you think the history of American education shaped your educational experiences? Pick 1-3 historical events / moments/ patterns to write about, and explain how they shaped your educational experiences. In answering this question, you must cite one course reading. |

Appendix B

Appendix C