Course(s): Bio 301 Plant Biology Lab

Department: Biological, Geological & Environmental Sciences

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor(s): Andrea Corbett (with preparation by Chris Rennison & Timothy Square)

Syllabus: b301 s21 syllabus – 01-19 version

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: 60-70 (Undergraduate, upper level)

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Blackboard, QR scanner apps, custom website hosting QR scanned information

Author Bio (50-100 words): Andrea Corbett has been an Assistant College Lecturer in the Department of Biological, Geological & Environmental Sciences since 2018, and was a part-time adjunct at CSU for 20 years before that. She has taught a variety of courses in Biology, including the Plant Biology lecture & lab every year since 1998. Chris Rennison is a Senior Instructional Technologist in the Center for Instructional Technology and Distance Learning. Timothy Square is the Superintendent of Grounds in the Office of Facilities Management.

Introduction – The importance of engagement & field experience in Biology Education

According to Cooke et al. (2021), there is a strong need for more trained ecologists & environmental scientists, but also non-biologists who have environmental knowledge. CSU is uniquely positioned to provide training related to urban ecology, as it is an urban campus with active research and teaching programs across several colleges including both Urban Affairs and the ecological and environmental science offerings within the Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences.

Experiences outdoors and “in the field” are a key component of biology and environmental science education (Thomas et al. 2017). It is important for biology and environmental science students to see living things in the places where they live – whether it be remote wilderness or urban gardens. Many ecological and environmental science careers require skills in identifying and counting species (Cooke et al., 2021). It is needed for questions related to studying diversity, conservation, and indicators of ecosystem health, for example.

In addition, field exercises can increase engagement through shared experiences (Zavaleta, 2020), which can not only produce better-trained scientists (Thomas et al., 2017) but also increase inclusion in ecological disciplines (Zavaleta, 2020). Full field courses, however, often come with extra costs, travel and extensive time commitment (Zavaleta, 2020), so an activity that can take place right on campus without those barriers could be a valuable stepping stone in a scientist’s education.

At CSU, one goal Andrea has for the Plant Biology course is to have students get outside at least once during their Biology degree. As CSU’s Superintendent of Grounds Tim hopes to get more students involved with the CSU Grounds Deptartment. The purpose of CSU’s Center for Instructional Technology & Distance Learning is to use technology in innovative ways to enhance student learning and Chris is a key resource person for this work. In early Fall 2018, Andrea met Chris and shared an idea to use technology to enhance an activity she had been thinking about creating for her class. We then invited Tim to join us when it became clear we wanted to use the campus tree map that Tim’s department “owned”. So, the three of us cooperated to produce an outdoor Tree Scavenger Hunt exercise for Bio 301 – Plant Biology Lab.

Setting the stage

In 2017, the CSU grounds department had an intern who used ArcGIS software (ESRI, 2015) to create an interactive map of campus. This map had an example tree for all 65 tree species planted on campus at that time, with a number assigned on the map and information about the tree species that popped up on the web page when a number was clicked.

In the fall of 2018, about 12 of those trees, most of which are native to Northeast OH, and selected to represent a cross-section of different biological plant groups, were chosen for the Scavenger Hunt Project for the Plant Biology Lab course. Andrea researched background information on range and features, sample photos of various parts of each tree were obtained from Wikimedia Commons (Wikimedia, n.d.), and the creation of a handout with instructions for students.

Chris took the lead on the technology side of the project, which took from late fall 2018 until March 2019. First, metal tags with key botanical information and a QR code were manufactured for each selected tree. This involved cutting black anodized aluminum into 3×5” rectangles, formatting the information to the right size and light text/dark background set-up, engraving the information and code using the Universal 48×24 laser engraver in CSU’s Maker Space, and then finishing the tag by smoothing edges and drilling holes for mounting on the tree.

(credit: Chris Rennison).

The second technology piece was to create the website that hosts all the information that is made available when a QR code is scanned. Information and photos from Andrea were added, short “bit.ly” links instead of long QR code links were generated, and the QR codes were created and connected to the correct part of the website.

In early Spring of 2019, Tim and his grounds crew attached the tags to the 10-12 trees that were part of the exercise, verifying that the trees were still alive (one wasn’t) and in the location indicated on the map.

(credit: Andrea Corbett).

The Student Experience

At the end of April 2019, on the designated day of the course, Plant Biology students were given the handout with their instructions (see Appendix 1). They were given a list of tree numbers from the map and followed these steps for each tree:

- Look up the tree number on the tree tour map website on a smartphone or tablet

- Walk to the tree location

- Find the tag and scan the QR code with a smartphone or tablet

- Make notes and observations about the tree to answer the assignment questions that are on the site that comes up when the code is scanned

- Take a selfie photo to prove you found the tree (goofy faces optional).

The student’s lab homework was to write up their answers to the questions for each tree and submit it (along with the selfie photos) to a Blackboard assignment on the course Blackboard page.

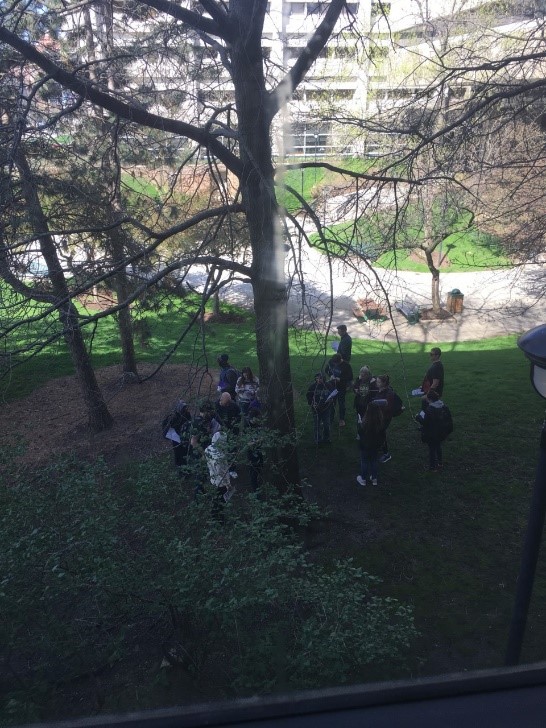

(credit: Andrea Corbett).

Outcomes

Students participated enthusiastically in small groups and reported enjoying the activity, as well as the opportunity to walk around campus. Many took the opportunity to take funny or goofy selfies with their group, providing a light-hearted way to build connections. Grades on the assignment were high and completion rates of the assignment were high, even though it was near the end of the semester.

(credit: Chris Rennison)

Future directions

The closure of campus due to COVID-19 prevented us from doing the activity in spring 2020. However, we were able to repeat it during spring 2021. Levels of participation and grades were high again, in spite of there being snow (!) on April 21, the day the activity was scheduled.

The “Tree Tour” map is being updated and reworked this summer by another intern, Shelby Seeberg, with the Grounds Department (who was also a Plant Biology student spring 2021). The hope is to make the map more three-dimensional, more accurate and include more information about the trees and the campus. As this work proceeds, Andrea is also hoping to add 6 more tree species to the Plant Biology assignment list that will expand the number of native species that are studied, with additional tags to be manufactured and affixed to those trees.

There is some interest by several groups across campus to have a tagged tree for every single species on campus and to make this information broadly available to the whole campus and the general public. Then these tags could be more widely used for people with casual interest, or for assignments in other courses that can use the tree information to ask their own questions.

__________

Citations

Cooke, J., Y. Araya, K.L. Bacon, J.M. Bagniewska, L.C. Batty, T.R. Bishop, M. Burns, M. Charalambous, D.R. Daversa, L.R. Dougherty, M. Dyson, A.M. Fisher, D. Forman, C. Garcia, E. Harney, T. Hesselberg, E.A. John, R.J. Knell, K. Maseyk, A.L. Mauchline, J. Peacock, A.P. Pernetta, J. Pritchard, W. J. Sutherland, R.L. Thomas, B. Tigar, P. Wheeler, R.L. White, N.T. Worsfold and Z. Lewis. 2021. Teaching and learning in ecology: a horizon scan of emerging challenges and solutions. Oikos 130: 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.07847

ESRI 2014. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.3. Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute.

Fleischner, T.L., R.E. Espinoza, G.A. Gerrish, H.W. Greene, R. Wall Kimmerer, E.A. Lacey, S. Pace, J.K. Parrish, H.M. Swain, S.C. Trombulak, S. Weisberg, D.W. Winkler, L. Zander. 2017. Teaching Biology in the Field: Importance, Challenges, and Solutions, BioScience, 67(6): 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix036

Wikimedia n.d. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page

Zavaleta, E.S., R.S. Beltran and A.L. Borker. 2020. How Field Courses Propel Inclusion and Collective Excellence. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35(11): 953-956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.08.005

__________

Appendix 1 – Bio 301 Assignment instructions:

Bio 301 Plant Biology – CSU campus tree scavenger hunt

Required materials: smartphone or tablet*, class handout, something to take notes on

Recommended materials: QR code reading app (Instructional Technology suggests ‘QR Reader for iPhone’ for Apple products & ‘QR Scanner’ for Android)

* if you don’t own a smartphone or tablet, you can pair up with someone who does, or you can sign one out from Mobile Campus

INSTRUCTIONS

- Using your smartphone or tablet, pull up the CSU Interactive Tree Map on the web browser. Use the Interactive Tree Map to determine the location of a tree on the list below. Walk to where it is on campus.

- Find the metal tag on the tree – use your phone/tablet to scan the QR code.

- Read the information that pops up on the linked web-page. Answer the 2 questions given on the web page (and save the link for future reference). A glossary of bark terms is included in this handout to assist with answering questions.

- Take a selfie of you and the tree/tree tag to prove you were there (group photos optional). Save your photos as small or medium files, to keep the size of the final assignment file reasonable.

- Repeat for each tree on the list

- Once you have visited all the trees, compile your selfies and question answers into a single file and save it as a PDF.

- Upload the PDF to the Tree hunt assignment on the Bio 301 Blackboard page.

DUE online TUES. APR. 27 at 11:59 pm

Here is the list of trees we are using from the CSU campus Interactive Tree Map (https://lcuacsu.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapTour/index.html?appid=9b8f6a7f8f5b40cf8f7205f20141316f#).

| 63* | White Fir |

| 9 | Pin Oak |

| 15 | Ginkgo/Maidenhair |

| 21 | Littleleaf Linden |

| 25 | Red Horse-chestnut |

| 34 | Red Maple |

| 35 | American Sweetgum |

| 38 | American Sycamore |

| 41 | Colorado Blue Spruce |

| 45 | Eastern White Pine |

| 64 | Eastern Redbud |

* Original hit by car – replaced by younger specimen at different location.

Bark description terms –

from Jay Hayek at https://www.extension.iastate.edu/forestry/tri_state/tristate_2015/Talks/PDFs/hayektree%20ID.pdf

- Smooth

- flat surface lacking in ridges, furrows, and similar features

- Horizontal lines (lenticels)

- Partially or completely raised lines that are often derived from lenticels in young bark

- Ridges

- vertical crests divided by intervening furrows

- uninterrupted or interlaced or broken

- Furrows

- vertical grooves separated by narrow or broad ridges

- Fissures

- regular or irregular cracks or crevices, narrower than furrows; may be vertical or horizontal

- Plates

- relatively large, distinctively circumscribed portions of bark; large and flat, small and blocky

- Peeling (exfoliating)

- separating into relatively large, thin, and sometimes curling plates or sheets

- Scales

- small, thin, often flaking plates

- Flaking

- separating into thin slivers, chips, scales, or shavings

- Shredding / Fibrous

- peeling in long, usually vertical, sometimes frayed strips or strings

- Corky

- visible corky or wartlike outgrowths

From: https://www.americanforests.org/magazine/article/the-language-of-bark/ by Michael Wojtech