Course: PHL 211 (Morals and Rights)

Department: Department of Philosophy and Comparative Religion

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Dr. Matthew Coate

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: roughly 40 first- and second-year students

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Powerpoint presentations

Author Bio: Dr. Matthew Coate is currently a Visiting Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Old Dominion University, and he completed his doctorate in Philosophy at Stony Brook University. He primarily teaches and does research on ethics and aestheticism and his publications, in which he largely employs the phenomenological method, includes articles on ugliness, John Rawls’s conception of liberal democracy, and the Japanese tea ceremony.

Abstract: As the pandemic approaches what we all hope will be its conclusion, we can now begin to reflect on the lessons that might be drawn from what is possibly the largest pedagogical experiment in human history, in order to try to “build back better” in the classroom. In my short reflection, I will focus on the lessons to be drawn from a single, and highly peculiar, pandemic-related pedagogical experience: namely, my experience of holding class discussions on the ethical considerations of pandemic-related public health measures, given that these very discussions were being shaped and constrained by some of the measures at issue themselves.

After describing the nature of these discussions and the context in which they unfolded, I will then discuss some of their unique features, including the following: the extremely timely nature of the articles around which our discussions were based, which had generally been published only weeks earlier; the extremely concrete nature of the examples that the class could turn to illustrate the issues under consideration, given that the discussion itself was carried out under the public health measures in question, as I just mentioned; and the extremely urgent, and relevant, nature of the matters under consideration. After discussing these features, and the way that each of them helped contribute to a spirited and trenchant discussion, I will finally discuss the lessons that I think we can draw from this unique case regarding the setting up of classroom discussions about current ethical and social issues more generally.

Keywords: Pedagogy; COVID-19; Bioethics; Synchronous Instruction

Like probably all of my readers, I had no experience of teaching in a pandemic before 2020 began. Had I known what we were all in for in advance, I imagine that I might have had a total breakdown and never made it to this point but would otherwise have been far more prepared for the pedagogical challenges that would soon confront all of us. And having now received a two-year-long crash course in teaching in these unprecedented circumstances, I’m quite sure that I’d be able to deal a lot better with the pedagogical challenges of another worldwide pandemic if another one of this magnitude were ever again upon us—although I think that a total breakdown would definitely be a live option in that case too.

Now I’m hoping, of course, that the cosmos doesn’t hate us quite so much as to throw another massive pandemic at us in our lifetimes, and that we’ll never have to use the experience that we’ve gained teaching in one to help us teach in another; rather, the lessons that we’ve learned will hopefully prove instrumental in improving our pedagogical practices as we return to something approaching normalcy instead. Crises bring danger with them, after all, but also the promise of renewal after the dust has cleared, and just as our current President has promised to “build back better” post-COVID, we might also hope for something similar in the field of education more narrowly, and particularly insofar as our pedagogical practices are concerned. We’ve just had two years to experiment with previously unimaginable forms of pedagogy, after all, and now find ourselves in a world beginning to return to normal and yet still reeling from COVID-19, in which just about every pedagogical option still seems to be on the table, so we’ll probably never have a better opportunity to bring about effective pedagogical reform and to establish new approaches that might help more of our students realize more of their potential than we could ever have imagined before. What lessons can we draw from our pandemic experiences that might be useful towards this end?

Since entire books could be written on this, I only propose to speak about the lessons I’ve learned from one pandemic-related experience: namely, my recent classroom discussion about the public health restrictions that have been established with the intention of reducing the spread of COVID-19. Because this discussion was not only timely and urgent but was also shaped by the very policies that were under discussion, I think that it constituted a quite singular occurrence. Nevertheless, I believe that I learned lessons from it that can be applied far more generally, and these are what I intend to bring to light now. After speaking about the discussion’s peculiarities, then, I’ll go on to discuss the general lessons that we might draw from the experience.

My Classroom Experience

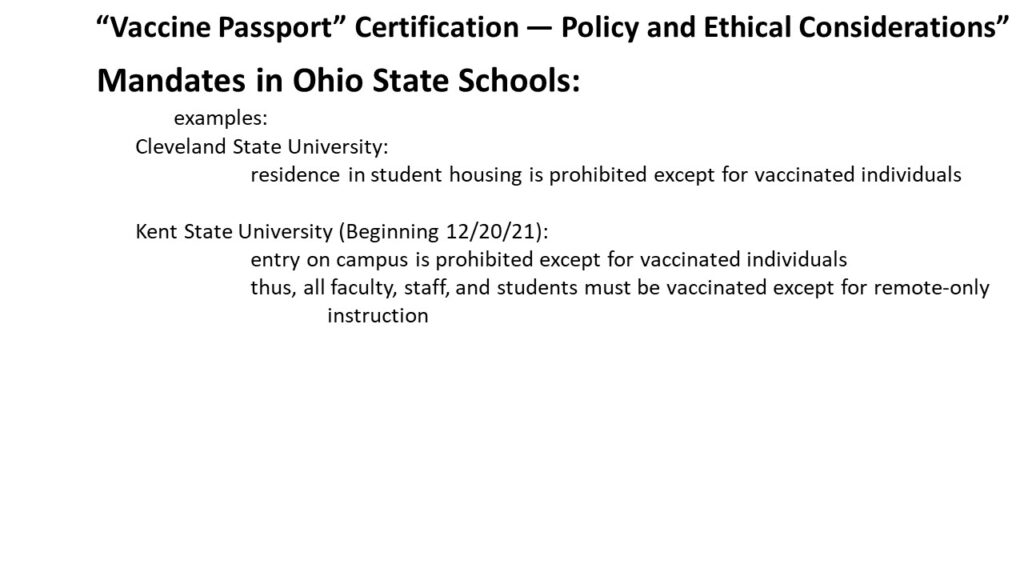

My classroom discussion on COVID-related public health measures took place as part of an applied ethics class held at Cleveland State University in the Fall semester of 2021, and was then repeated in a section of the same course this Spring 2022 semester. The course, titled “Morals and Rights,” is intended to provide a quick survey of theories in normative ethics, which the students then employ to help think through various pressing moral, social, and political issues that we go on to discuss for the greater part of the semester. Typically, some of these are issues related to healthcare ethics, but instead of tackling abortion or euthanasia, as would typically be the case for a class of this type, I decided (quite sensibly, I think) to look at issues pertaining to the COVID-19 pandemic, and so I assigned a number of articles addressing the various public health measures that we’re largely calling “mandates” these days, and particularly, vaccine mandates. My students read these articles, submitted short summaries about them, and then attended class meetings in which we discussed the relevant policies in some depth.

As I noted earlier, these discussions were peculiar for a number of reasons. The articles that we read, for one, were likely more recent, relative to the class meetings in which we discussed them, than any articles my students had been assigned for any classes they had taken previously. COVID vaccines had only become available that spring, after all, and people had only really begun to seriously consider vaccine mandates the summer before my Fall 2021 class, so articles on vaccine mandates in particular had generally begun seeing publication only weeks before the beginning of our class. In fact, I had difficulties finding relevant peer-reviewed articles at all, given that the peer-review process isn’t one that has ever been accused of being speedy—and especially not in the humanities, where preprints aren’t really a thing—so I had to turn to editorials in newspapers like the Times and Wall Street Journal to gather a well-rounded sample of perspectives. The result of all this is that the students got to enter into a dialogue that was only beginning to unfold as our discussions took place.

The discussions weren’t only peculiar because the articles that framed it were so new, however, but also because the issues we were discussing were of the most pressing nature imaginable. Now sometimes I imagine that my students will find a certain topic relevant only to discover that they aren’t especially enthralled by it—one time in particular I wrote the word “sex” as enormously as I could on my classroom blackboard and hardly saw a student bat an eye—but there was no way that we could discuss COVID-related public health measures and, particularly, COVID-19 vaccine mandates without my students getting passionately involved. The discussions remained civil, but it was clear that my students felt that they had a real stake in the issue and whether they argued for or against these mandates, or even were highly ambivalent about them, none of my students failed to understand the great relevance of the debate.

However, the most peculiar feature of our discussions about pandemic-related public health measures was surely the fact that these discussions were taking place in a venue governed or otherwise shaped by these very measures. All of the participants, for one, were wearing our masks as mandated, and in the Fall 2021 semester, most of us were just returning to fully in-person classes after more than a year dealing with variations on remote learning. The school itself had other pandemic-related measures in place, such as mandated social distancing on various parts of campus and a vaccine mandate for students residing in the school dormitories, in which a number of my students lived at this time. Given this unprecedented dynamic, there was a certain “meta” element to our discussion—at one point one of my students struggled to be understood because of the mask that she was wearing as she spoke to the class about how mask-wearing can make classroom discussion more difficult—and this made the relevance of the issues we were discussing all the more obvious. Surely no student will fail to understand the importance of discussing pandemic-related measures when many of the effects that the measures have on us are ubiquitous in the very classroom in which they’re being discussed.

I hope it’s obvious, now, that my classes’ discussions of COVID-related public health measures were quite singular occurrences. Now that I’ve distinguished some of the peculiarities of this discussion, though, and examined how they motivated my students to get more involved in it, I’m going to try to draw some lessons from all of this that might be applied more broadly, for although these advantageous peculiarities were built in, as it were, to my classes’ discussions on COVID-related measures, it might prove helpful to see if there’s some way to exploit the same dynamics in other classroom discussions, in which these dynamics wouldn’t appear to be inevitable features of the discussion itself.

Lessons Learned from the Classroom Experience

What are the lessons that I’ve been able to draw from these COVID-based discussions, then? In the first place, I’ve begun to think about how recent, or not recent, the articles are that I assign for my classes, and particularly for my classes on applied ethics. Like most instructors who teach these courses, I have a strong tendency to assign the “classics” in the field, and sometimes nothing else besides; and I often think of these “classic” articles as being quite recent, in fact, given that I was, say, already in high school when many of them were published. Yet my students, who didn’t even exist as a thought in their parents’ minds when I was in still high school, hardly think of these articles as “recently published” ones, and are probably right not to think of them this way in fact, given the ever-increasing speed of change that we find everywhere in our world, and the effect that social and technological changes have had on even long-standing social and political issues and crises. For this reason, I believe my students would be better served if I at least mixed in recently published articles with the “classics” when I put together my classes’ list of assigned readings.

By the same token, I’ve also begun to think more about whether or not the issues I ask my students to grapple with will be deemed pressing ones by their own lights. At times I’ve resisted the push to “make things relevant” for my students, given that one of the major objectives of a liberal arts education is to broaden our students’ minds, and broadening here must at least partly mean getting our students to take an interest in various matters that they would never have taken to be relevant before. This is especially so when teaching moral philosophy, I think, given that more than all else, the hope in ethics is (or at least should be) to get students to consider the interests and well-being of those who they may not have thought very much about before—matters will hardly have appeared “relevant” to their own lives previously. Yet there’s something to be said for at least meeting our students halfway, and after seeing how my students took to a discussion that they undoubtedly already found relevant on some level I’ve come to appreciate that a lot more.

Finally, I’ve learned how instructive it may be to highlight the ways that the issues that I’d like my students to discuss in our class meetings actually shape our very classroom and their experiences in it. Sometimes this may not be possible, given that the matter to be discussed may not be one that has any real effect on our classroom and what goes on in it; yet mostly I think we’ll find that it does have such an effect, but that I just never thought to bring this up before. Never before have I begun a discussion on environmental crises, for instance, by pointing at the light fixtures overhead and speaking about the bulbs that are illuminating the classroom, or by speaking about the building materials that have been used to construct it; nor have I begun these discussions by asking my students to tell me how they arrived to class, or to think about how students in other parts of the world travel to school and how they themselves might travel to school if our world was a little different. Yet all of these matters are surely connected to our ecological crises or to our attempts to address them; and if nothing else, discussing them could provide an “in” for my students to begin to recognize the relevance of the discussion. So just as I’ve been able to draw valuable generalizable lessons from my reflections on the other two peculiar features of my classes’ recent discussions about pandemic-related public health measures, I’ve also found that reflecting on this last peculiarity of these discussions has helped me to learn how I can engage my students more fully in our classroom discussions per se.