Course: English II

Department: English

Institution: Lincoln West School of Science and Health

Instructor: Taylor Zepp

Number & Level: 71, 10th grade students

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Schoology, GoogleDrive, GoogleSlides, GoogleDocs

Author Bio: Taylor Zepp is a sixth-year English II teacher at Lincoln West School of Science and Health. Additionally, she advises an underclassmen YPAR club and serves on the school’s Social Emotional Learning (SEL) committee. Prior to her time at Lincoln West, she taught at East Technical High School and spent one year with Youngstown City Schools. She is a 2016 graduate of the University of Akron, where she previously published.

Abstract

Academic gaps have been at the forefront of the conversations surrounding K12 education and the pandemic. However, this loss goes far beyond academic skills. Students in today’s classrooms have had the past three years of their education disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. The 2021-2022 school year’s students in Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) returned after a year and a half of remote or hybrid learning. These students are facing increased anxiety, grief, and uncertainty. They have also lost time where they would have been learning social and emotional skills in the physical classroom.

Project-based learning (PBL) provides the unique opportunity to be a way to deliver academic content while building connection and community within the classroom. Though there are more logistical struggles in today’s pandemic-era classroom, the academic and social benefits outweigh the logistical struggles in the planning process.

This case study will examine a unit completed by tenth-grade English Language Arts students studying Shakespeare’s Othello at Lincoln West School of Science and Health in the 2021-2022 school year. I hope that this case study will show that project-based learning is still accessible in the pandemic-era classroom.

Introduction

When Governor Mike DeWine enacted stay-at-home orders in March 2020, education changed overnight. Two years later, things still have not returned to “normal.” The 2021-2022 school year was the first move back into the full in-person classroom for all Cleveland Metropolitan School District students after a year and a half of online and hybrid models. Even so, the pandemic has still affected the classroom. With increased absences, shifts to temporary online learning, and general uncertainty, in-person learning is not what it was before.

Preliminary data shows there has been academic learning loss during the Covid-19 pandemic. A study based on NWEA testing data showed that “in the elementary grades (where widened gaps were most evident), gaps increased by roughly 20% in math and 15% in reading” (Kuhlfeld et al. 8). These gaps are even wider in low-income school districts, like CMSD (Kuhlfeld et al. 7). Preliminary findings from Cleveland shows, “in the CMSD, chronic absenteeism in the 2020–21 and 2021–22 is double pre-pandemic levels” (Education Forward). They also noted that students have reported increased levels of stress and lack of support (Education Forward).

However, academic learning loss is only part of the story. The pandemic has majorly disrupted children’s lives, with many facing “psychosocial consequences”(Crescentini et al). With so much time out of the traditional school setting, students lost many of the non-educational things that school offers. For many students, schools are also a provider of social services. For example, CMSD provides meals, internet, and other social services to its 35,696 students. Beyond this, schools are a space of socialization, and what students experienced online is not comparable to the in-person classroom experience.

The social-emotional effect of this is palpable. “I feel like mentally we’re all still eighth graders,” said one of my tenth-grade students. She feels that the lack of in-classroom experience has hurt some of her peers. “It’s like we never had that first year of high school, so we have to do all of that now,” she added. Even national studies show an, “increase in instances of verbal and physical fighting, behavioral referrals, and mental health concerns as students returned to in-person learning in the fall of 2021” (Education Forward).

In my personal experience, the class of 2024 entered this school year less prepared to work with peers and didn’t have as many of the soft skills I would typically see. A year and a half of Zoom and desks facing six feet apart with no group work had taken a toll. I knew I had to do something to attempt to fill this gap. That is where project-based learning entered the picture.

What is PBL?

When I was introduced to the concept of project-based learning, I wasn’t convinced. I was worried that given the uncertainty of the pandemic I would not be able to successfully implement an extended group project. However, PBL felt different than the structure of other end-of-unit projects I had done before. Unlike a traditional group project, “PBL requires critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and various forms of communication” (PBLworks). These are all skills that are incredibly important for students, especially when they have lost so much time in the in-person classroom.

I have since completed three PBL units this school year: creating dystopian societies, Crime Scene Investigation: Othello, and a youth participatory action research (YPAR) cycle. This case study will focus on the second.

Crime Scene Investigation: Venice

As my tenth-grade classes completed Othello, I set out to design our second PBL unit of the year. The result was titled: Crime Scene Investigation: Venice. Students were broken up into groups where they took on the role of criminal investigators, looking into one of the several homicides and suicides at the end of the play. They entered the classroom to an announcement stating “There has been a murder in Cyprus.”

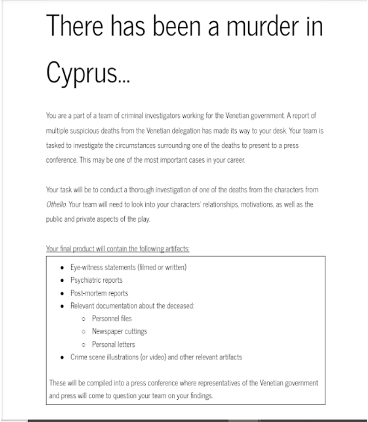

Students received an entry document that stated the following: “You are a part of a team of criminal investigators working for the Venetian government. A report of multiple suspicious deaths from the Venetian delegation in Cyprus has made its way to your desk. Your team is tasked to investigate the circumstances surrounding one of the deaths to present to a press conference. This may be one of the most important cases in your career.

Your task will be to conduct a thorough investigation of one of the deaths from Othello. Your team will need to look into your characters’ relationships, motivations, as well as the public and private aspects of the play.”

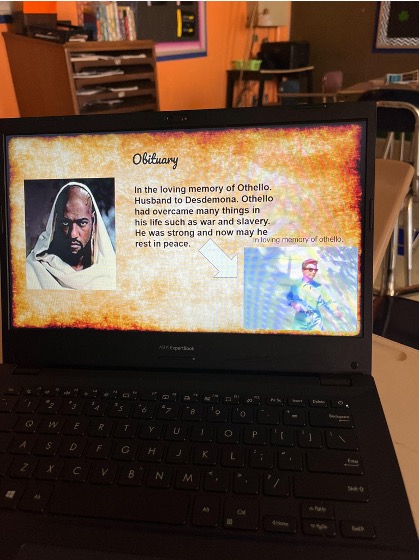

Also included was a list of the “artifacts” students would be responsible for generating as a final product. These serve as checkpoints as students work their way through the project. The artifacts students were to create included: eye-witness statements (filmed or written), psychiatric reports, post-mortem reports, employee personnel files, newspaper articles, personal letters, and crime scene illustrations (or video). This work culminated in a mock press conference of each group’s findings.

Navigating Group Work During a Pandemic

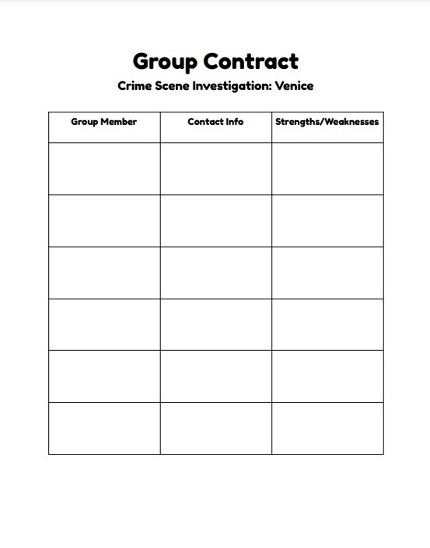

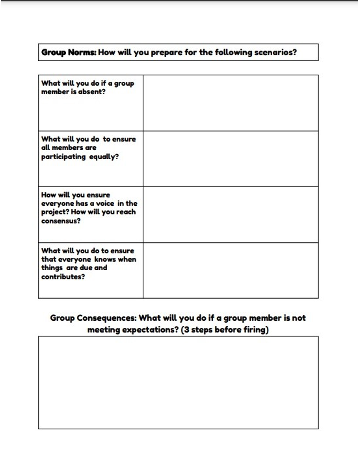

Before any work on the project started, we spent a class period setting group norms and expectations for teamwork. To set the groups up for success we created group contracts. Using a modified contract I adapted from Lattes and Lit, students worked through a document that required them to identify their strengths and weaknesses, contact information, solutions to scenarios that they may face, and what steps they will take before a classmate is “fired” from the group (Lattes and Lit). Having a set of consequences and rules before a project begins reduces the need for this in the first place and lowers student stress.

This document has been crucial for successful group work, especially given the increased absences we have seen in the wake of Covid-19. Students were able to create group chats using Instagram, facetime with members who were at home, and could send work to each other because they were required to share contact information. It also required students to set procedures for when a member was inevitably absent. By creating these plans before any problems arose, all group members were able to feel as if they were a part of the decision-making process and set a universal expectation.

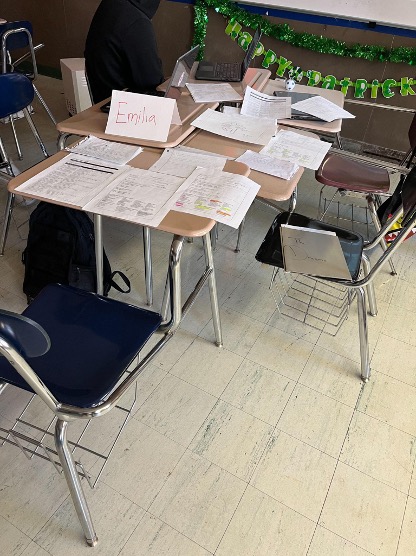

Another way we were able to navigate the challenges of increased absences was by having all project checkpoints available as something that could be done on paper or digitally. This made it easier for absent members to continue to work with their group asynchronously. Each group had a folder that housed all of their paper documents in the classroom in addition to shared documents in GoogleDocs, allowing students to work in the ways that made them feel most comfortable. Some groups worked on paper, whereas others completed everything online.

I have found that flexibility is crucial in our current climate, but is also best practice as we move into the post-Covid world. The time spent in the remote and hybrid environment equipped students with the digital skills and autonomy to take ownership of their learning even more than those who came before them.

The Outcomes

After approximately three weeks of class time, students were able to show their mastery by conducting press conferences. School community members were able to visit the classroom and speak with each team. The teams were responsible for summarizing their findings, displaying and explaining their created artifacts, and answering any questions from the “press.” At the conference, we made sure to follow Covid-19 precautions.

While grades and work completion rates increased during this project, the biggest shift I noticed was in the characteristics we try so hard to target through social-emotional learning. Behavioral problems dropped drastically due to students setting rules and enforcing their group norms. Students were forced to problem solve with others and to collaborate, even when it was sometimes uncomfortable.

Most importantly, students took an active role in their learning. They moved out of the receiving role, a tendency in the early stages of online learning, to taking the majority of the responsibility. All of the frameworks of the CASEL social-emotional-learning framework (self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationship skills, and social awareness) are built into the framework of a successful PBL unit (CASEL).

Conclusion

I am not here to say that project-based learning is the solution to the myriad of problems we face as we adjust to a more typical classroom experience. However, it can be a part of the puzzle. Many, if not most, of the students in our classrooms have been impacted emotionally by the pandemic. They may be uneasy being back in the in-person learning environment and may have some gaps in the social skills we would expect them to have had the past two years been more typical. Project-based learning provides a way to seamlessly weave social-emotional learning into academics, creating a better experience for us all. The skills learned through PBL will help them succeed in the classroom and beyond.

Works Cited

Crescentini, Cristiano, et al. “Stuck Outside and inside: An Exploratory Study on the Effects of the Covid-19 Outbreak on Italian Parents and Children’s Internalizing Symptoms.” Frontiers, Frontiers in Psychology, 22 Oct. 2020, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586074/full.

Kuhlfeld, Megan, et al. “Test Score Patterns across Three COVID-19-Impacted School Years.” EdWorkingPapers, Brown University, Jan. 2022, https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai22-521.pdf.

Lattes and Lit. “Dystopian World Creation Project-Based Learning Unit (Now with Digital Handouts).” Dystopian World Creation Project-Based Learning Unit (Now with Digital Handouts), Teachers Pay Teachers, https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Dystopian-World-Creation-Project-Based-Learning-Unit-Now-with-Digital-Handouts-4401789.

“The Impact of Covid-19 on Cleveland’s Education Landscape.” Education Forward, May 2022. “What Is PBL?” PBLWorks, Buck Institute for Education. https://www.pblworks.org/what-is-pbl. “What Is the Casel Framework?” CASEL, Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning , 11 Oct. 2021, https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/.