Course: Ethics of Collaboration and Developmentally Appropriate Practice: Birth to 10

Department: Education

Institution: Hiram College

Instructor: Jen McCreight

Number & Level: 25 students in Ethics of Collaboration (Education course opened up to campus, counts as a core requirement in the area of Ethics and Social Responsibility, first year to senior level students enrolled); 10 students in DAP: Birth to 10 (Education course for P-5 Elementary Licensure and Educational Studies students, typically at the sophomore level)

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: None specifically applicable here, but in the courses, we utilize iPad Pros, Apple TVs, Moodle, and many related apps/presentation tools.

Author Bio: Jen McCreight is an Associate Professor of Education interested in family/school partnerships, validating the diverse linguistic backgrounds of students, and incorporating technology into classrooms to enhance and deepen learning. She enjoys learning from and with her students and gravitates toward discussion-based and interactive class sessions. Dr. McCreight has published and presented with students, as well, and continually looks for opportunities to engage them in collaborative research. Additionally, she prioritizes relationships with local schools, through service learning, field visits, and clinical experiences. These relationships challenge Dr. McCreight to be a more innovative and reflective educator in her work with college students.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has worn on, I have felt its impact nowhere more deeply than in my continually re-worked, re-vised, and re-configured courses.

Each time I believe I have cracked the code, that I have figured out what my college-aged students and pre-service teachers need as learners and emerging educators, I find myself in even more uncharted territory, realizing yet again that the effects of the pandemic have turned what I previously considered to be effective pedagogy into a moving target.

This is HARD, I find myself saying again and again. But when I am uncertain, I can return to the table and try once more, I have found that what helps me to put one foot in front of another is to humbly practice deep listening and reflection. In this essay, then, I will describe pedagogical shifts that have come only from pausing, taking a breath, and connecting with/learning from my students, myself, and our shifting needs. I will focus on concrete examples related to broadening assignment format options and adjusting course policies, with an eye toward focusing on evolving student needs and equitable access to the curriculum. And in doing so, I hope to begin a conversation focused on support, growth, and – ideally – renewal.

Broadening Assignment Format Options

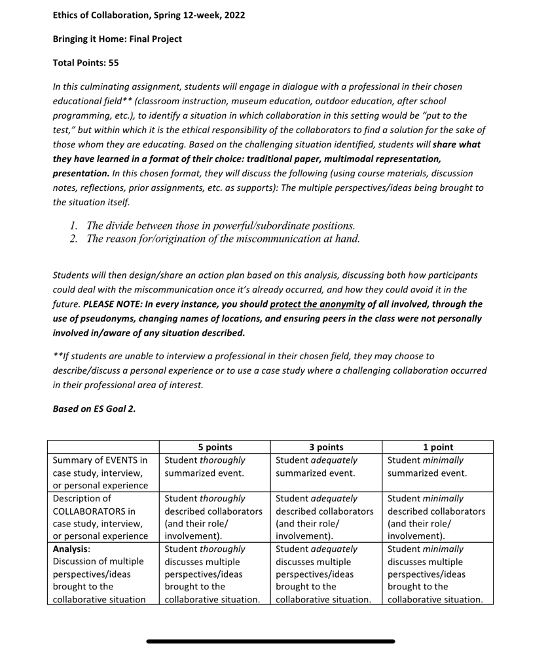

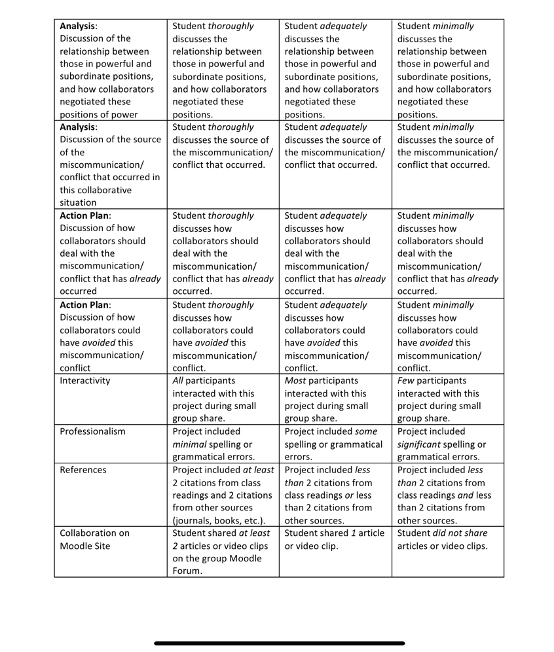

I’ll begin with an anecdote regarding a class I teach on collaboration within educational settings, entitled Ethics of Collaboration. Students from across the college participate, so I often work with people majoring in environmental studies, history, management, or integrative exercise science. As part of my commitment to model effective collaboration, it is my practice in this course to share with the class the rubric [see Figure 1] for our final project, and ask them to make any changes they believe would increase the effectiveness of the project. Most often, this discussion results in only slight changes/shifts to the assignment itself, and at times it has even felt like a formality.

This year though, was different.

Around the fourth week of class, my students clustered into groups, analyzing the project’s rubric. The assignment focused on students identifying a collaborative situation where a miscommunication has occurred and using course content to reflect on and improve the issue at hand. Because of the collaborative and communal nature of the class, each student shared their work in the form of a presentation. I walked around the room, listening to students as they conversed. Most said the assignment did not need further adjustment or editing, and that they agreed with the format and content as an appropriate way to share their learning. I nodded at each of these exchanges, noting this agreement and expecting to move through the whole-group discussion quickly.

“Okay,” I began, calling the small groups back together. “Let’s talk. What do you think needs to change?”

The room was initially quiet. And then, a student near the front of the room raised his hand, and said quite simply, “Does it have to be a presentation?” I paused. Did it?

“Well…it always has been. But I suppose not – tell me more about what you are asking.”

He went on to share that his group had noticed that the learning objectives of the rubric could be accomplished through other modalities, such as each student writing individual papers, instead of giving presentations. I felt myself push back a bit, even as I saw others in the class perk up, and nods begin to spread across the room.

“How, though, do we share what we have found in our projects? How can collaboration happen when your audience is me?”

We were back in person, after all, and had an opportunity we had not had in years – to share what we were learning in meaningful ways. This was non-existent through Covid. I didn’t want to take a step backward. I took a breath, though. Did it have to be a presentation? These students – who in many cases had lacked the ability to make educational decisions for themselves throughout the pandemic due to restrictions of movement, required remote learning, and cancellations of important events and experiences – were demonstrating agency and engagement in re-creating an assignment I had assumed was fine. Yet, who was I to assume I knew what was best – especially now?

Upon further conversation, I came to realize that the students were not shying away from sharing. Instead, they embraced the possibility of sharing their work in small groups, but simply wished to broaden the ways in which they could demonstrate their learning. What was once, then, an assignment I had always envisioned within the confines of a presentation, became a multimodal opportunity for students to creatively demonstrate their analytical and creative capacities to work through collaborative challenges.

Our assignment sheet changed to reflect this, making clear they could enact their final projects as in-person presentations (as originally designed) – or, they could choose to write a paper, create a screencast, design a website, or even build a mind map. Student buy-in and engagement with the final project audibly increased after this conversation. In fact, through anonymous midterm feedback on how the course was going, one student shared, “The only thing I had an issue with was the final assignment, and now that’s changed – so everything is going well.”

Additionally, I found students were not only engaging with the content of their presentation but were also wrestling meaningfully with the modality in which they would share it. “I thought at first a paper would be easiest,” I heard from a student after class one day, “but when I started thinking about this particular project, I realized it would be best to discuss it through an in-person presentation.”

The day the projects were shared, four students chose to do so in the original format, giving formal presentations in front of the class. The other twenty formed small groups and took turns sharing with their peers. I heard a hum of discussion throughout, with each member listening intently to one another, and commenting on what they were learning/the questions that were being spurred through their peer sharing. Afterward, I asked the class whether the format changes we made should stay in future years, and was met with emphatic nodding.

“Why?” I prodded, interested in their responses.

“Because it allowed for greater creativity,” some said.

“I learned a lot from each of my peers in a small group, and am taking a lot with me,” someone else chimed in. “If we’d all done separate presentations, I would have been overloaded with info, and would have possibly learned less.”

In a time, then, when students are continuing to pinpoint who they are as creators and learners, and to come together in community to find meaning and value in their educational experiences – entering into this space of authentic give-and-take in assignment creation resulted in not only a positive classroom environment but will now be an option for future groups to pick up (or edit out!) for themselves. I’m looking forward to seeing what will happen next time around….

Adjusting Policies

I’ll now focus on a moment that took place in a teacher licensure course, which led to a shift in my attendance and assignment due date policies. Similar to what unfolded in my collaboration class, these policies changed as a result of intentional listening. I will begin by stating that, for years, I maintained a consistent attendance and assignment policy. It read something like this:

Because you as teachers will expect regular attendance and participation from your students, I in turn expect the same of you. Due to the interactive nature of this course and because the assignments build upon one another, you will be expected to attend class each day and to turn in assignments on time. Unexcused absences and late submissions will result in deduction of ___ points from your total grade.

This was largely unquestioned, by my students or by me, partly because attendance and timely work submission was typically a non-issue. They generally attended, communicated when they could not, offered doctor’s notes when appropriate, and emailed ahead of time if an assignment was going to be turned in even a few minutes after the deadline. And then Covid became part of our landscape, and students’ worlds were turned on their heads.

Family commitments took rightly precedence, illness or worry about illness began to cause more frequent absences, and once the world began to open back up, students’ work commitments ramped significantly in order to recoup resources they were unable to earn in the early throes of the pandemic. Students were stressed. Mental health concerns were high. Faculty were stressed. Our own mental health concerns were high, as well. How do we acknowledge the challenges facing our students and our broader community, we wondered, while still moving our classes forward in dialogic, discussion-oriented, and experience-focused ways? Even as restrictions lifted, and maybe even especially as restrictions lifted, challenges related to attendance and work submissions rose.

Even as students and faculty expressed joy and relief in knowing our courses would be in-person this semester, fewer students made it to class every day. I knew there was a disconnect. I didn’t know what it was. And that was hard for me. In this frustration, I once again listened and reflected. I turned to my students, asking them in class one day what had changed about their learning, their academic and personal challenges, since Covid came into our lives? They offered many insightful responses, but I wish to focus on one, because it was this one that caused the puzzle pieces of understanding to begin falling into place.

“During the early days of Covid restrictions,” a student began, “we were all at home. We had more downtime than we ever had, and we were isolated. This made us anxious and sometimes depressed.”

There were nods around the room.

“And then this year, we are back in-person, and we want to engage,” they continued, “but our bodies and brains are so used to the inertia, to the practice of waking up five minutes before class to turn on a computer Zoom screen, that we are struggling to meet the demands of what used to be a given – you wake up in time to get to class in-person, and you give yourself enough time to submit assignments by their due date. And these challenges, this inability we are feeling to make these things happen even in majors we care a lot about – this is causing a different kind of stress and anxiety than the earlier phases of our pandemic life.” It was here, in this conversation and in that moment, that something clicked. Here was the insight I had struggled with and failed to ascertain myself. How could I, really? When my pandemic experience occurred at such a different juncture of my life?

I realized that my prior structures and policies were likely adding unnecessary stress to students who were truly working to re-engage with the world, and who cared deeply about their work within it. If I could loosen these structures, I needed to do it.

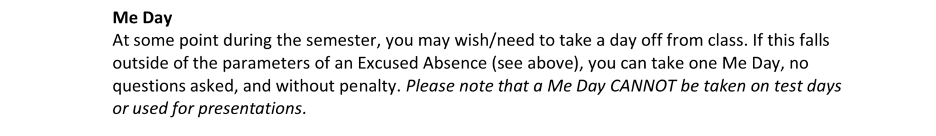

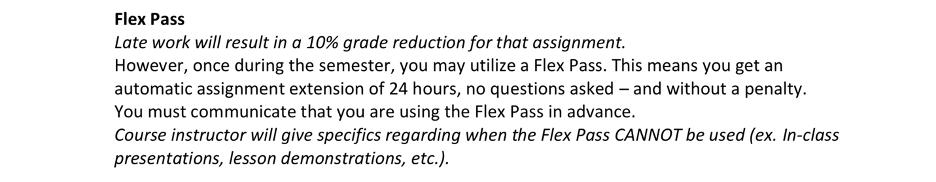

This is why my syllabi now includes one Me Day and one Flex Pass for all students.

The Me Day functions as an excused absence, no questions asked – students simply email me prior to class, to let me know they won’t be there. It is designed so they don’t feel the responsibility of sharing personal details should they have to miss class for any reason, while also acknowledging that things come up, and sometimes those things occur during class – and that is okay.

The Flex Pass provides a student with an additional 24 hours to complete an assignment of their choice throughout the semester, with no late penalty. While I continue to think it’s a critical skill for future educators to submit their work on-time, given that they must be present and prepared in their day-to-day working life, I also know that it is very rare for me to grade a submitted assignment the day after it is turned in. Therefore, this additional 24 hours may mean the world to a student who had something come up that kept them from finishing – but the time given still allows our course to move forward for all learners at a reasonable pace.

Now that these policies have been in place for a semester, I have heard feedback from multiple students that they appreciate them for the stress and anxiety they alleviate, allowing them to fully complete the work at hand without compromising their mental well-being. Students from my previous courses have heard about this through the campus grapevine, and have made it a point to tell me the policies would have been very useful to them in the fall – which is great fodder for a discussion as to how all educators, myself very much included, should learn and grow each year, and should expect their reflection on challenges and successes to lead to improved classroom practice.

I will keep these policies, far beyond the reach of Covid. I will keep them because they are more responsive to students and their needs in this time and place – and, because I owe it to my current and future students to shift what I do in the classroom as a result of their input.

Moving forward into the coming academic year, I will continue to listen and reflect, recognizing that the challenges Covid has placed on educational settings have fundamentally changed faculty’s and student’s understanding of effective pedagogy at all levels. This means that we must engage meaningfully in interrogating our practice, as we grow into and move through this new teaching world.