Course: Political Science 394/Art 395

Department: Political Science

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Jeffrey Lewis

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: 17 upper-level undergraduates majoring in Political Science and/or Art

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Blackboard, PowerPoint, Email

Author Bio: Jeffrey Lewis is Professor of Political Science at Cleveland State University, and Department Chair since 2020. His research focuses on International Relations and political economy, with a specialization in the European Union (EU) decision-making process.

Abstract: In Fall 2022, I offered a new interdisciplinary course “Politics & the Graphic Novel” at Cleveland State University. The course was cross-listed as a Special Topics elective in Political Science and Art History (PSC 394/ART 395), and combined a mix of undergraduates from both academic fields. The main pedagogical goal was to study the comic art form as a way to apprehend important contemporary issues with significant future implications for social and political change. By focusing on a set of exemplar graphic novels covering themes such as—economic insecurity, the malleability of cultural memories, organized protest and state violence, dehumanization, war, state failure, and patterns of societal-level apocalypse—the course embeds “politics” into a more liminal space that sheds light on big canvas themes of crises and change from multidisciplinary perspectives. The vernacular of comics presents a distinct medium to perceive agency-structure relations between large-scale political, economic, social, cultural, legal, and historical processes of change and the micro-foundational level of human agency that is implicated in them. By reading a wide sample of graphic novels and studying the medium itself, students learned about politics through comics. What difference can that make? Based on the outcome of this course, the substantive content of politics in graphic novel form can speak emotional truths, establish humanizing forms of empathy through “masking” and perspective-taking techniques, and generate real interdisciplinary insights into intangibles like collective identities and memories.

The medium of comics, particularly the long-form “graphic novel,” offers ways of comprehending politics in all its messy richness that some might find surprising. Surprising that is if what you equate as “comic books” are simple stories of superheroes, Manichean notions of good versus evil, or fantastical worlds of escapist fiction. Today the comic art form represents a rich body of output produced across the globe in a daunting array of styles and genres. Whole subfields include, for example, comics journalism (such as Joe Sacco’s ethnographic conflict zone fieldwork), graphic medicine and healthcare, thematic anthologies, and memoir or autobiographical comics covering every nook and cranny of the human condition. The graphic novel and comics form is no longer doubted as a legitimate part of the literary canon, and major publishing houses have taken notice as comics have evolved into one of the most dynamic growth segments for readership at all different age ranges and demographics.

Convinced that comic art is a distinctive, value-added way of seeing and knowing the world around us, including the weight of the past and possible futures, I set out to develop an upper-level undergraduate elective course, “Politics & the Graphic Novel.” [See Syllabus below]

Pedagogically, the aim in developing the Special Topic class was to anchor the substantive content of comics in the same interdisciplinary, boundary-spanning analytical spaces that appealed to me as a graduate student and have informed how I understand and think about politics ever since—an approach known by various labels such as Historical Institutionalism or Historical Sociology.1

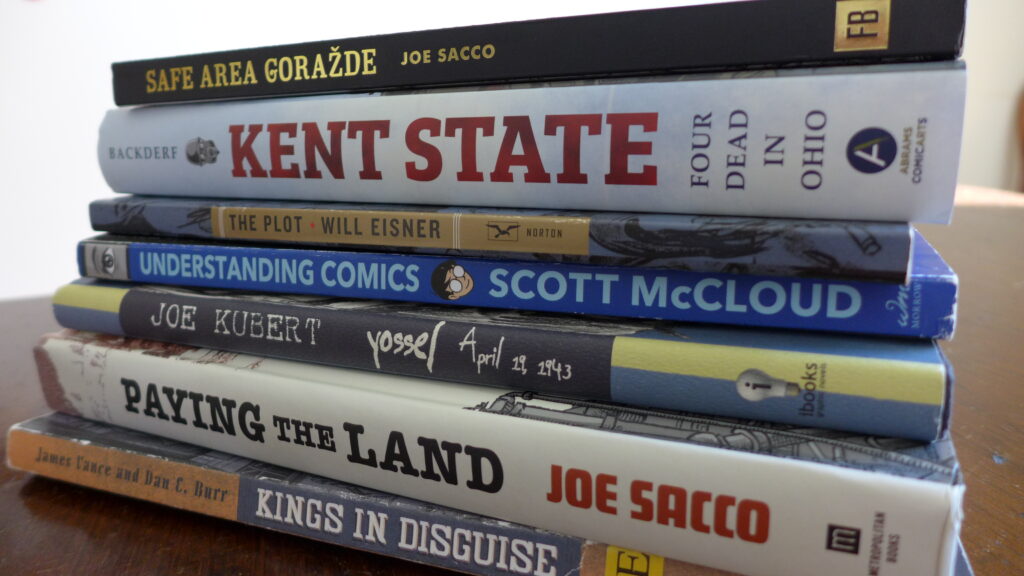

When designing the course, my first decision was to avoid assigning “mega” classics such as Maus and Persepolis since some familiarity with this material would be likely.

Selecting graphic novels that few if any of my students would be familiar with seemed a good strategy to stimulate collective learning and discussion from a level playing field of no a priori assumptions or exposure. I also wanted the course to explore a range of comic art forms to relay a sense of the cultural globalization that cartoonists are fashioning today; in other words, a set of readings to constitute eclectic exemplars rather than follow a grand theory or focus (such as a whole course on “war comics”). The course organizes major topical themes commonly found in Political Science and especially the areas I work in, International Relations (IR) and International Political Economy (IPE). The themes include:

- Economic insecurity, crises, and society

- Cultural assimilation, repression, and memory

- Organized protest, state violence, and accountability

- Conspiracy, myth, and dehumanizing the “other”

- War, state failure, and patterns of “apocalypse”

For each theme, I decided on an exemplar graphic novel [see syllabus and Figure 1]. A common denominator is the nexus of state-society relationships across time and space that illustrate how patterns of authority and legitimacy evolve especially as societies encounter hard times or experience collective traumas. Each exemplar depicts historically accurate representations of human agency caught up in some larger scale event or change process whereby the medium of comics innovates novel ways to imagine and contextualize perspective-taking (or what is called “masking”). By masking into a war zone or economic meltdown or organized protest, readers gain an emotional truth and empathetic understanding of what sectarian or political violence or material deprivation might actually feel like which is a distinct way of grasping big canvas history and the politics of how societies evolve. Within the reading selections, my pedagogical interest in historical institutionalism shows up again and again in the way agents and structures interact to suggest a patterned “social ontology” for thinking about politics and state-societal relations.2

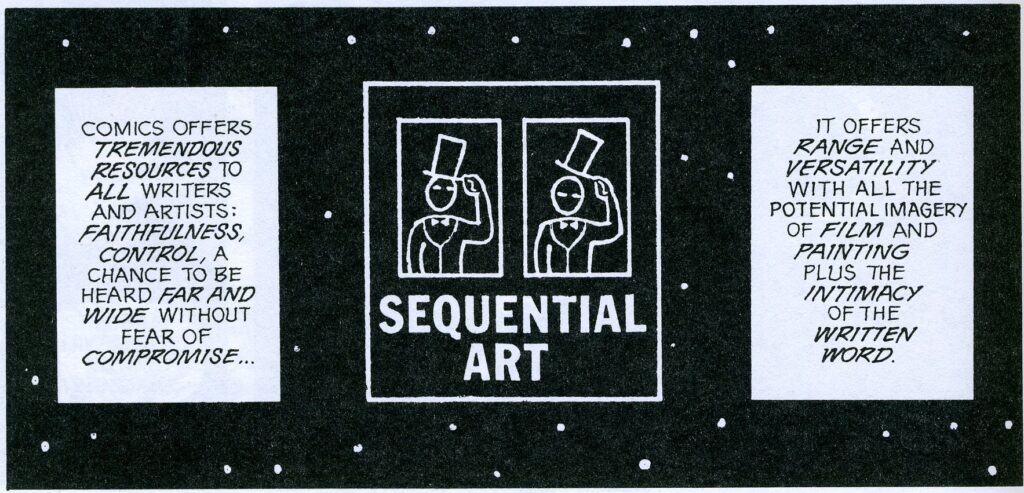

A second intentional design choice was to anchor the class in the vernacular and techniques of comics art and the growing field of comics studies.3 The authoritative work by Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics,(a graphic novel about the graphic novel) is laudable for both accessibility and sophistication. In continuous print since first published in 1993, McCloud’s survey of the comic form is noteworthy for how fresh and undated it remains, and his insights can appeal to a wide spectrum of newbies and experts alike. As a standard reference work on how to read and apprehend the “sequential art” form (Will Eisner’s preferred term for comics), McCloud’s analysis is suitable for audiences from young adult to college-level instruction (see Figure 2).

The course experience itself resulted in some pleasant discoveries. For one, it was refreshing to have a combined group of undergraduates from Political Science and Art, with the students engaged and listening to each other during our class discussions in what seemed different from the usual academic silos class discussions operate from. We had technical discussions of cartoonists’ drawing styles and paneling techniques, and compared artists across topics. The iconography of facial expressions, the strategic use of the “splash page,” the changes in scale and pacing, the masking techniques for perspective-taking, the visual impact of negative space, the design choices involved with word balloons, lettering, and so on. We also made connections to current events and “real world” politics, such as how economic insecurity correlates with public health and today’s ongoing opioid crisis (and “deaths of despair”4), or the differences in how society treats PTSD now compared to WWII or the Vietnam era. Or comparisons between “cases” such as: failing states (Yugoslavia in the 1990s with Lebanon today), or organized state violence (America’s Civil Rights and Vietnam era with Ukraine’s Maidan Square or China’s Tiananmen).

Students were required to write two short research papers (2,000 words each) along with weekly reflection essays (700 words each) on additional readings and questions that I assigned (more on reflection essays below). Paper 1 focused on a comics study analysis utilizing Scott McCloud’s work and Paper 2 focused on a current events analysis related to politics. Students were allowed a high degree of autonomy in selecting books or topics for the research papers, based on themes or material they wanted to explore in more depth. To help guide them to think about sources for the research papers, I included a longer listing of “other honorable mention comics” and “other recommended further readings” for each main topic in the syllabus. My objective was to extend the range of material students were exposed to in the course and to make explicit the multidisciplinary richness of our thematic topics from different corners of the Humanities and Social Sciences. The creative range of ideas and topics found in this collective set of papers stands out as one of the more memorable classes I have taught (and learned from) over the last few decades.

Another unexpected, pleasant outcome was my realization of how powerful the graphic novel can depict historical memory. The combined imaginative freedom that words and images juxtaposed in deliberate sequence can produce, provides a distinct narrative grammar for the study of collective memory and how memory politics can resonate across time. All of our main readings cover this. As a fictionalized account of an orphaned teenager experiencing the Great Depression and encountering the entire range of humanity from life on the road, Kings in Disguise is ineffably timeless in capturing the lived feeling of economic insecurity and its attendant social dislocations that might qualify how one thinks about the aspirational “American Dream.” Paying the Land is a tour de force account of state-societal relationships in Canada regarding Indigenous communities and how social, cultural, economic, and environmental traumas transmit intergenerational legacies with macro/structural and micro/agent implications for the present. Kent State shows a near-forensic account of the long weekend culminating in the infamous campus shooting by the Ohio National Guard but also captures how fraught broader state-society relations had become during that time, as well as the unsettling conclusion that public accountability for this societal trauma has never been achieved in the national psyche. Kubert’s Yossel is a harrowing counterfactual of the Holocaust centered on the liquidation and uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto, and what fate the alter cartoonist-as-child might have endured had his family’s emigration to the United States not worked out, giving the reader an unparalleled angle into collective memory functions by a “survivor” who escaped such a fate. The Plot traces the pernicious conspiracy theory behind the so-called Protocols of the Elders of Zion to Europe’s revolutionary era of 1848 that became weaponized by the Russian tsar in 1905, and readers learn just how shockingly immune this exposed fakery has been to dispel from social consciousness despite being debunked over and over and over again. Finally, Safe Area Goražde offers a participant-observer ethnography of Eastern Bosnia during the implosion of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, and, using testimonial evidence, richly connects a societal apocalypse to toxic us/them forms of “othering” lodged deep in the cultural memory banks of the Balkans’ ethnonationalist identities.

Each weekly “module” of the course paired our graphic novel exemplar with supplemental readings and comics that required students to write an approximately 700-word “reflection essay” due each Friday. We spent two or three weeks per graphic novel (alongside reading sections of McCloud), which allowed reflection topics to probe or connect themes in additional ways. The content of material for the weekly essay topic was deliberately varied to alternate short news articles or video interviews with other comics. For example, when reading the 1930s Great Depression storyline of Kings In Disguise, I assigned an excerpt from Susumu Katsumata’s Fukushima Devil Fish depicting the precarious occupational hazards for nuclear power plant workers known as “irradiated laborers” or “nuclear gypsies” in order to contemplate today’s range of taken-for-granted employment practices and inequalities.5 When reading Kent State, I contrasted student-protester perspectives with a mini-comic based on a first-hand war experience, Tapestries, brilliantly scripted by Alan Moore to depict the fractures of American society from the time-split perspectives of a boy raised in middle-class suburban Pennsylvania who is drafted and sent to Vietnam, with a problematic return home to “normality.”6

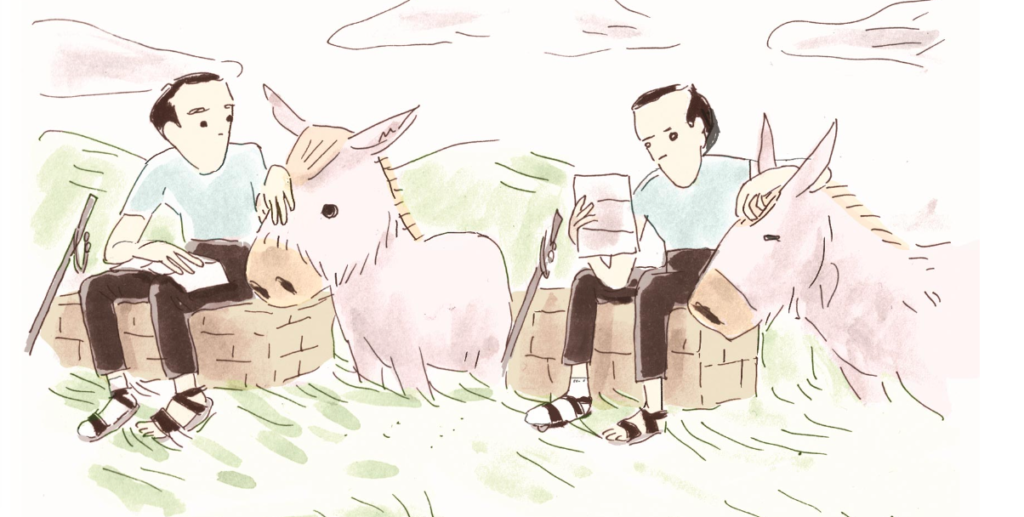

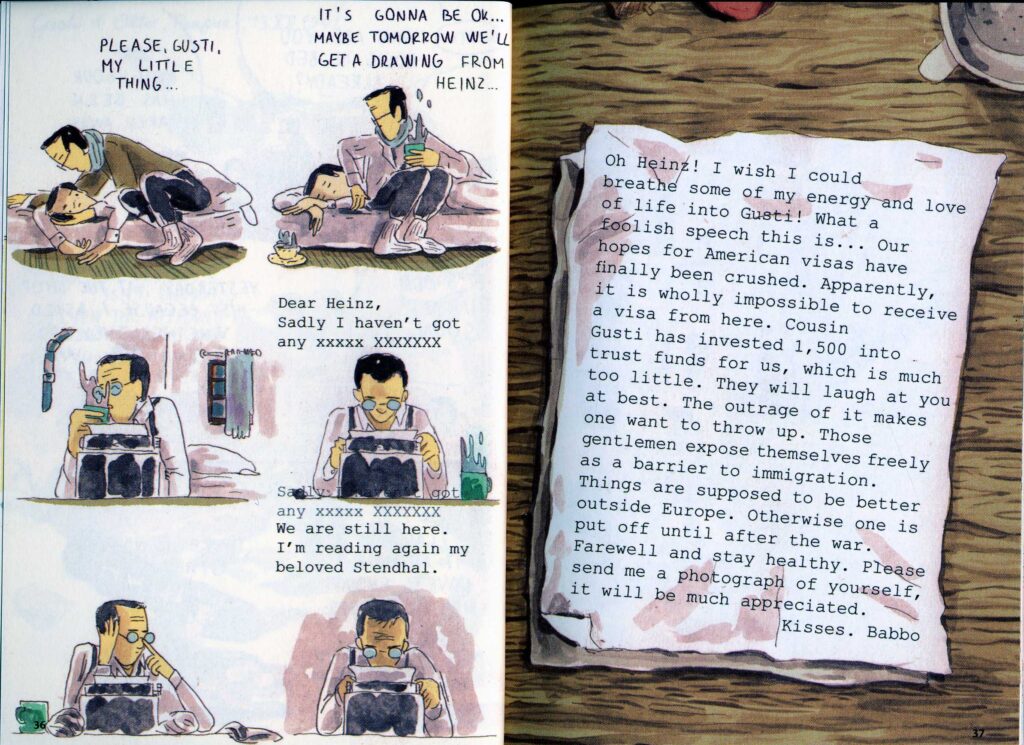

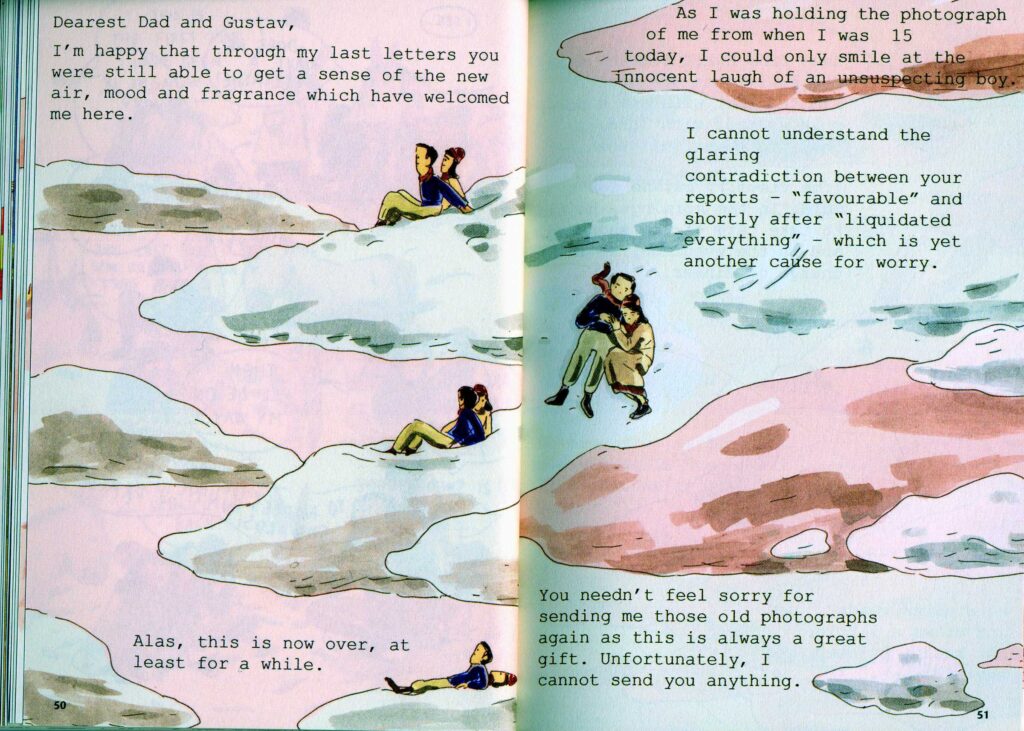

A particular class favorite was our supplemental reading of Alice Socal’s Pink Donkeys.7 This remarkable mini-comic is part of a multidisciplinary project “Redrawing Stories from the Past,” focusing on the traumas and memories of WWII as a result of National Socialism.8 Using a variety of approaches and cartoonist styles, the stories are designed to “illustrate an unseen, forgotten and marginalized part of our collective memory.”9 In Socal’s Pink Donkeys, readers follow the wispy traces of one Viennese Jewish family’s atomization by the forces of Nazism through surviving letters and family archives. Her visual style depicts the loss of identity and mental stresses they endure (even a kind of self-obliteration, see Figure 3) while facing vast isolation with the unknowable fates of loved ones.

The central character, Heinz Skall (above), is trying to remain in touch with his Mother and Father (each remarried with different partners) after deportation to the comparatively obscure Southern Italian internment camp in Campagna where he draws and paints, and communicates with a figment of his imagination, the eponymous pink donkey (see Figure 4).

Heinz survives the war, but his parents do not. A culminating moment in the story occurs when his former letters are returned as undeliverable, with the unspoken realization of what grim outcomes must have befallen them. Socal’s soft color palette and the floaty, cloud-like contextualization of the back-and-forth correspondence voices a palpable sense of felt distance between family members.

We are reminded we’re studying historical memories in her panels as the main characters’ faces are drawn without mouths—their erasure underscores how the dead can no longer speak directly in the unchangeable past.

The paneling is non-linear and the storyline is purposely discontinuous—time is out of joint—enhancing the ethereal qualities of how memories often seem to flow. After our initial discussion of Socal’s work, I realized how helpful the collected volume’s postscript by Ole Frahm was in providing contextual background to Pink Donkeys.10 By making Frahm’s postscript available for the class to read, subsequent discussions were enhanced and I was impressed at the effort students made in drawing out the inferential connections in the Skalls’ story.

The documentary evidence embedded in her panels, such as reproductions of Heinz’s sketches and watercolor paintings as well as excerpts from actual letters gives a personalized touch to this drama that enhances the masking effect and emotive power of one family’s wartime experiences. Pink Donkeys as sequential art conveys a story from the annals of historical memory that words alone could not reveal. Our class discussion flowed freely on how Socal’s techniques produced such insightful qualitative research, an exemplar of the multidisciplinary potential for understanding that this course was designed for. To accentuate the micro-macro, agency-structure theme of WWII’s quotidian dislocations, the next time this class is offered, I would consider pairing Socal’s Pink Donkeys with some reading selections from Mark Mazower’s epic overview, Hitler’s Empire.11 To contrast the granular scale of the Skall family to the macroscopic scale of civilian harm from WWII would help punctuate the emotional truths that Pink Donkeys so powerfully captures.

Overall, the new Special Topic offering “Politics & the Graphic Novel” was a positive learning experience. The students who enrolled learned a wide range of substantive content covering politics but from new angles and ways of comprehending the real world that the comics medium can distinctly offer. Based on this experience and student feedback, the course is likely to be regularly offered every other year as a cross-listed elective option (so next up in Fall 2024). The sequential art form itself holds much promise for interdisciplinary thinking and insight into the complexities of the human condition as states and societies evolve and change over time.12 Above all else, the endless creativity that comics are capable of can be intellectually stimulating to think about large-scale issues and patterns of change in new ways.

Want More? Further Reading—If Theda Skocpol’s historical institutionalism and the imagination of the comics art form appeals to you, a few further graphic novel exemplars are worth exploring:

- Jason Lutes (2020) Berlin (Drawn & Quarterly). With the original three volumes now in compendium form, you can experience the Germany of the 1920s and 1930s from a range of perspectives. The agent-structure relationships in this work showcase what is perhaps the most tumultuous state-society sequence democracy and its antithesis has yet to produce.

- Timothy Snyder and Nora Krug (2021) On Tyranny (Ten Speed Press). A graphic adaptation of Snyder’s text with Nora Krug’s gorgeous visual design to contemplate the lessons of authoritarianism and fascism in new light for thinking about how history can or might not repeat itself.

- Igort (2016) The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule (Simon & Schuster). A stellar research design that captures historical memory on an epic scale, made all the more hauntingly relevant in 2023.

Footnotes

1The course syllabus contains additional narrative detail on the “new institutionalism” approaches that my Special Topics framing relates to. For good overviews of Historical Institutionalism and/or Historical Sociology (oversimplifying just a bit, both labels are attributable to the Theda Skocpol “school” of “new institutionalism”), see Peter A. Hall and Rosemary C.R. Taylor (1996) “Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms,” Political Studies, XLIV, pp. 936-957; Colin Hay and Daniel Wincott (1998) “Structure, Agency and Historical Institutionalism,” Political Studies, XLVI, pp. 951-957; Peter A. Hall and Rosemary C.R. Taylor (1998) “The Potential of Historical Institutionalism: A Response to Hay and Wincott,” Political Studies, XLVI, pp. 958-962; Theda Skocpol (ed.) (1984) Vision and Method in Historical Sociology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); Sven Steinmo, Kathleen Thelen and Frank Longstreth (eds) (1992) Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press); Paul Pierson (2004) Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

2 In Karl Marx’s famed phrasing of “historical materialism”: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” Karl Marx (2008/1852) The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (New York: International Publishers). My usage of “social ontology” here derives from Hay and Wincott, supra note 1.

3 Thanks to Samantha Baskind for her suggestions on developing this aspect of the course.

4 Anne Case and Angus Deaton (2021) Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

5 Susumu Katsumata (2016) Fukushima Devil Fish: Anti-Nuclear Manga. Translated by Ryan Holmberg (Breakdown Press). See also, Ryan Holmberg (2015) “Nuclear Gypies,” Art in America, December, pp. 114-19. A downloadable PDF of this article is available from Ryan Holmberg’s extensive website, https://mangaberg.com/.

6 W.D. Ehrhart and Alan Moore (1987) “Tapestries: Part I and II,” in Real War Stories #1 (Forestville, CA: Eclipse Comics), pp. 10-16. With art by Stan Woch, John Totleben, and S.R. Bissette; lettering by Mindy Eismen; and colors by Sam Parsons.

7For more on Alice Socal’s work, see her website, https://www.alicesocal.de/. To read more about the context of Socal’s Pink Donkeys project, see, http://www.alicesocal.de/comics/comic/pink-donkeys-redrawing-stories-from-the-past/. A high-resolution digital version of Pink Donkeys can be viewed by clicking on the link “Read the comic on DRAWING THE TIME,” or available here, https://drawingthetimes.com/story/pink-donkeys/?fbclid=IwAR0MaaeAToxwjR1NsM4ijL9Fj-IpQ_dhUfBBt5sPunNiSTudrVGB9gfYo3U.

8To date, this project has published two special volumes in the long-running comics anthology series, S! (or Baltic Comics Magazine). The original volume is Redrawing Stories From the Past(2015), Baltic Comics Magazine, S!, #23. The second volume (which includes Pink Donkeys and cover art by Alice Socal) is Redrawing Stories From the Past II(2019), Baltic Comics Magazine, S!, #34. For more on S! and related publications by Kus!, see, https://www.komikss.lv.

9From the issue preface, Redrawing Stories From the Past II(2019), Baltic Comics Magazine, S!, #34, pg. 3.

10Ole Frahm (2019) “The Spectres of Escape,” Postscript from Redrawing Stories From the Past II(2019), Baltic Comics Magazine, S!, #34, pp. 208-221.

11Mark Mazower (2008) Hitler’s Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe (New York: Penguin Books).

12See also, Jeffrey Lewis (2023) “Comics Art, Cultural Norms, and the Social Consciousness of Activism in American Democracy,” Cleveland State Law Review, Vol. 71, No. 4, pp. 983-1028. A downloadable PDF is available from the CSLR website: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol71/iss4/