Course(s): EDU 6390: Classroom Instruction & Assessment for Language Learners

Department: Teaching and Learning

Institution: Southern Methodist University

Instructor(s): Dr. Jillian Conry, TA – Ann Marie Wernick

Syllabus (submitted as PDF):

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: Master of Education class (n=16)

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Mursion mixed-reality simulations

Author Bio (50-100 words): Ann Marie Wernick is a Graduate Research Assistant and doctoral candidate at the Simmons School of Education and Human Development at Southern Methodist University. Her research interests coalesce around understanding and supporting teacher learning for both pre-service and in-service teachers. She is particularly interested in designing collaborative learning spaces for teachers to enact skills, receive feedback and construct knowledge. Before her time at SMU, Ann Marie earned her M.Ed. from the University of Notre Dame, and was a classroom teacher and instructional coach. Ann Marie moved back to Ohio in summer 2021 and is finishing her dissertation work from the Cleveland area.

Abstract

Mixed-reality simulations offer pre-service teacher (PST) candidates opportunities to link theory with practice in a low-stakes environment. Within a semester-long course focused on preparing teacher candidates for working with culturally and linguistically diverse students, three mixed-reality simulations were embedded to support teacher learning. The simulations were created through a design-based approach and data was collected from video recordings of the simulations, debrief conversations, surveys and classwork. Feedback from both teacher educators and teacher candidates helped inform the subsequent simulations within this learning cycle. Preliminary data suggest small group debrief conversations following simulation enactments provide teacher candidates with a common context to self-reflect, unpack a learning experience and ideate on ways to improve their practice.

Introduction

With a commitment to providing pre-service teachers (PSTs) with opportunities to enact instructional activities, collaborate with their professors and colleagues, and receive feedback on their teaching during coursework, we turned to mixed-reality simulations (MRS) to help PSTs enact instructional activities and reflect on their practice. In particular, with the advent of Covid-19 and limited opportunities for our PSTs to enact teaching within schools, we set out to understand how embedded MRS simulations within coursework could help foster and propel learning for teacher candidates. This case study is a reflection of how MRS simulations coupled with coursework can offer teacher educators a powerful tool to support novice teachers, in the pandemic era and beyond. Before we describe our work, we want to highlight our own subjective positionality. Our work is informed by our past experiences as K-12 educators and our current work as teacher educators. It is through these experiences that motivated us to pursue this research.

Pedagogies of enactment to support teacher learning

Over the last forty years, teacher coaching has become an integral component of educators’ professional learning. In this study, we, two teacher educators of Classroom Instruction & Assessment for Language Learners, view teacher coaching broadly and define it as anytime coaches and peers observe teachers’ instruction and provide feedback to help them improve. Teacher coaching is now commonplace within schools and teacher preparation programs in response to Joyce and Showers finding that ongoing coaching resulted in 80 to 90 percent of new practices being implemented within schools (Joyce & Showers, 1981). Due to the complex nature of classrooms, it is not surprising that there has been an uptick in coaching with its ability to couple practice with feedback. As Ronfeldt (2014) acknowledges, teachers who complete more practice teaching feel better prepared in their first year. Within teacher education, teacher educators, expert others, mentors and peers are frequent providers of feedback (Grossman, 2009). In response to the push for more opportunities to practice teaching, teacher preparation programs have worked to embed more practice into their coursework to better prepare PSTs for field experience. In particular, pedagogies of enactment, have been incorporated into coaching cycles as this shift towards practice-based teacher education has emerged (Forzani, 2014). While pedagogies of enactment can take many forms, mixed-reality simulations are one tool that can enhance teachers’ utilization of instructional strategies through practice related to their individual needs. As Grossman (2005) acknowledges, teaching is a complex practice, learned over time, through rigorous and deliberate study combined with thoughtfully orchestrated opportunities to practice. Hence, mixed-reality simulations provide a unique space where teachers can practice instructional activities in a low-stakes environment to help PSTs hone their skills before entering the classroom (Mikeska & Howell, 2020).

Learning in a community of practice

In order to unpack what was happening within the debrief conversations between the three simulations during the course, we pull on the “community of practice” framework to help identify trends that emerged during the debrief conversation between the teacher candidates and coach who was the teacher educator. The sociocultural theory emphasizes that the ability to see is not determined by an individual but established within a community of practitioners (Chaiklin & Lave, 1996). Communities of practice are common within educator preparation, as novice teachers work with teacher educators, mentors, and peers to build a community of practice centered on making sense of ambitious teaching (Kazemi et al., 2016). Within a community of practice, feedback forms the basis of regular critical reflection and allows for ongoing examination of current understandings in the domain, expanding the knowledge of the community and contributing to its future development (Han, 1995). To engage novices in the work they need to learn in a community of practice, the teacher educator works to establish and maintain relationships with and among novices, one by one, in small groups, and as a whole class (Lampert & Ghousseini, 2012). In considering feedback, the community endeavors to draw on the collective experience and understandings of individuals within it, along with theory and new information, to critique current practice, in order to improve and progress its knowledge base and practices (Daniel et al., 2012). Positioning novices as responsible and contributing members of the community of practice and creating opportunities (pedagogies of enactment) that develop their competence can afford them a sense of authority and accountability for their learning (Greeno, 2007; Lampert et al., 2013 & Kazemi et al., 2016). In particular, Hammerness and colleagues (2005) argue that novices are more equipped to enact practices effectively when clinical experiences are carefully designed for them to learn “content-specific strategies and tools that they are able to try immediately and continue to refine with a group of colleagues in a learning community” (p. 375). Embedding pedagogies of enactment into a community of practice framework recognizes that learning to teach requires that novice teachers participate in instructional relationships in ways quite different from what they likely experienced as students, challenging them to rethink key ideas and values associated with those experiences (Ghousseini, 2017).

Methods

Setting and Participant

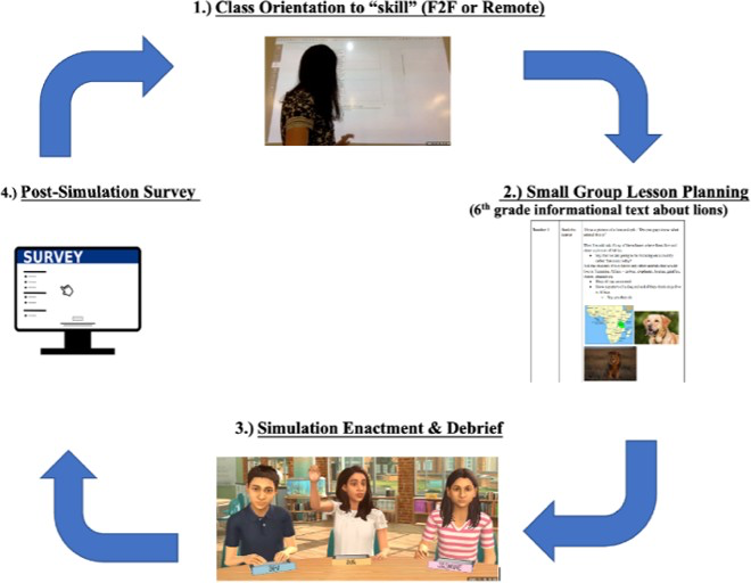

The setting for this exploratory study was a masters-level education course for pre-service teachers that focused on working with culturally and linguistically diverse learners. Our analysis focuses on sixteen (N=16) teachers who were enrolled in the course and participated in all three embedded mixed-reality simulation scenarios during the semester. Teachers’ grade levels and content areas spanned EC-12, History, ELAR, Science, Math, and generalist certification areas. The three simulations scenarios embedded into this course utilized the Amplifying the Curriculum: Designing Quality Learning Opportunities for English Learners lesson model (Walqui & Bunch, 2019) with each simulation focusing on a different aspect of the learning model: preparing the learners, interacting with the text, and extending understanding. Figure 1 illustrates the general sequence of events during the course.

First, the teacher candidates (TCs) were oriented towards a part of the lesson cycle (1st – preparing the learners, interacting with the text, and extending understanding during class, 2nd – they had time in their small groups (2-4 teacher candidates) to plan their lesson for the simulation, 3rd – the teacher candidates enacted the simulation and participated in the debrief, and 4th – the teacher candidates participated in a post-simulation survey. The pedagogy of enactment was an approximation of practice. Within the three lesson cycles (preparing the learners, interacting with the text and extending understanding) the lesson foci were chosen to support teacher scaffolding of lesson material to support English language learner (ELL) students and to build on each prior simulation experience. Additionally, the lesson foci sequence was chosen to span grade levels and content areas in order to meet our teacher candidate’s needs.

Data and Analysis

Three data sources were collected for this study: surveys, zoom recordings and coursework documents. First, two surveys were administered, one being a demographic/PST population survey, and another was the post-simulation survey which was collected after each of the three simulations. Second, zoom recordings of the class lessons before the simulation enactments and the zoom recordings from the MRS simulation and debrief conversations. Third, the lesson plans for each simulation were collected along with the chatbox from each simulation session of the TCs sharing their noticings and wonderings from their sessions.

After several rounds of inductive coding, data was analyzed using content analysis methods. The constant comparative analysis method (Corbin and Strauss, 2015) was then used to identify coding categories. Within the coding categories, we looked for episodes of pedagogical reasoning (EPRs) to analyze learning opportunities within interactions, or the moments where there were moments of teacher-to-teacher talk (Horn, 2015).

Findings

The process of thinking collaboratively can result in collective or public knowledge, but the intelligence behind this dynamic is individuals engaged in reflective discourse with the goal to construct personal meaning but collaboratively confirm understanding (Garrison, 2015 p. 13). Several trends and patterns from our coding of the debrief conversations emerged, including, how and when teacher candidates made connections with students, the grain size of the scaffolding teacher candidates used to support student understanding and how accessible the language used by the teacher candidates was to the students.

In the interest of space, we focus on several interactions from making connections with students below. This excerpt illustrates a few salient episodes of PSTs thinking about and discussing how to make connections with students. These episodes also illustrate how they are learning in a community of practice and engaging in reflective discourse.

Debrief Excerpt from November 2020 Class Period

B – Yeah, the first thing I noticed was that the students were very curious and intrigued with all the information P was sharing, I think they really appreciated all the extra facts related to the text. It really drove their curiosity. I wonder if P would have had them go to a specific sentence/or chunk that would have helped them answer their questions more. Kind of what P was talking about right before with the review, if that would have ended up helping them.

TE – What do you think P since you were the one in there?

P – It felt like to me that the students were having trouble connecting to the text um even though they had read it. I needed to dial it back and make it more specific.

TE – that is interesting, and it gets to the deconstruction of the text and how much scaffolding is needed to help them deconstruct.

H – Kinda a little bit of what B noticed, students were super engaged, and you engaged with every single one of them and their interests, like Jasmine and her interest with her shelter work and Ava the size of Connecticut and Dev always interested in something. You did a good job of involving all students and gave good wait time. I wonder and I had this issue two weeks ago, was getting Jasmine to engage more than with one- or two- word answers. I noticed that when you asked her about the disease from dogs and she answered with contact, a good follow-up question might have been how or think about how we can provide more follow-up questions for Jasmine

TE – That is interesting H, Jasmine made a connection at the beginning of the lesson showing she understood the text, but she didn’t give us a lot of language production in her response. H said follow up questions, any other ideas?

P – Yes, when I came back with the hyenas, she perked up and talked more

TE – Why do you think that was?

P – It was something she could relate too, she recognized and was familiar with

TE – good noticing

K – I had the same wondering as H and it was something, I struggled with during my first simulation, and I noticed like P said, she was very comfortable and confident with sharing about her love of animals and I wonder if we could find a way to get her to connect to something, she has experience with first and then ask her context-based questions to help her expand her responses. I also loved the connection you made with Dev about being sick and the balance of engagement between all 3 students was awesome. B – Brianna TE – Teacher Educator P – Patrick H – Hannah K – Kristina

B – Brianna

TE – Teacher Educator

P – Patrick

H – Hannah

K – Kristina

Within this excerpt of the debrief conversation, the teacher educator/coach and PST delve into what they noticed about how the lesson went with regard to making connections with the student avatars. Further, this community of practice allowed for critical discourse where PSTs and the teacher educator could press each other on how the lesson unfolded.

Conclusion

This exploratory study aims to contribute to the field in three ways. First, the study will impact practice by supporting PSTs in learning in a community of practice. Second, the knowledge gleaned from data analysis will inform future research by serving as an exploratory study for this collaborative learning cycle with mixed-reality simulation including identification of beneficial/productive elements of virtual professional learning. Third, policy implications may emerge related to clinical formats for teachers with instructional technology integration, and in the fluid context of the pandemic. Overall, MRS has provided teacher educators a tool they can leverage to embed practice opportunities within coursework and supplement field experience for teacher candidates when field experiences are limited such as was the case with Covid-19. In particular, MRS affords teacher candidates opportunities to practice specific instructional activities with the ability for “do-overs” in a low-stakes controlled setting. Moving forward in a post-pandemic era, MRS will continue to provide a low-stakes environment for teacher candidates to practice instructional activities, receive feedback and refine their teaching.

References

Chaiklin, S., & Lave, J. (Eds.). (1996). Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Cobb, P., Confrey, J., DiSessa, A., Lehrer, R., & Schauble, L. (2003). Design experiments in educational research. Educational researcher, 32(1), 9-13.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Daniel, G. R., Auhl, G., & Hastings, W. (2013). Collaborative feedback and reflection for professional growth: preparing first-year pre-service teachers for participation in the community of practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2013.777025

Forzani, F. (2014). Understanding “Core Practices” and “Practice-Based” Teacher Education: Learning From the Past. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533800

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. Routledge.

Ghousseini, H. (2017). Rehearsals of Teaching and Opportunities to Learn Mathematical Knowledge for Teaching. Cognition and Instruction, 35(3), 188–211.

Greeno, J. G. (2007). Toward the development of intellective character. In E. W. Gordon & B. L. Bridglall (Eds.), Affirmative development: Cultivating academic ability (pp. 17-47). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Grossman, P. (2005). Research on pedagogical approaches in teacher education. In M. Cochran- Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Review of research in teacher education (pp. 425-476). Washington D.C.: American Educational Research Association. Gundel, E., Piro, J. S., Straub, C., & Smith, K. (2019). Self-Efficacy in Mixed Reality Simulations: Implications for Preservice Teacher Education. The Teacher Educator, 54(3), 244–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2019.1591560

Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re‐imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 15(2), 273-289.

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Berliner, D., Cochran-Smith, M., McDonald, M., & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In L. Darling- Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world. What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 358-389). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Han, E.P. (1995). Reflection is essential in teacher education. Childhood Education, 71(4), 228 230.

Horn, I. S., & Kane, B. D. (2015). Opportunities for professional learning in mathematics teacher workgroup conversations: Relationships to instructional expertise. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 24(3), 373-418.

Joyce, B. R., & Showers, B. (1981). Transfer of training: The contribution of “coaching”. Journal of Education, 163(2), 163-172.

Lampert, M., & Ghousseini, H. (2012). Situating mathematics teaching practices in a practice of ambitious mathematics teaching. Investigação em Educação Matemática, 5-29.

Lampert, M., Franke, M. L., Kazemi, E., Ghousseini, H., Turrou, A. C., Beasley, H., Cunard, A., & Crowe, K. (2013). Keeping It Complex: Using Rehearsals to Support Novice Teacher Learning of Ambitious Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(3), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487112473837

Mikeska, & Howell, H. (2020). Simulations as practice‐based spaces to support elementary teachers in learning how to facilitate argumentation‐focused science discussions. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1356–1399. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21659

Ronfeldt, M., Schwartz, N., & Jacob, B. (2013). Does pre-service preparation matter? Examining an old question in new ways. Teachers College Record, 116, 1–46.

Smith, T & Garrett, R. (2020, April). Simulated Instruction in Mathematics Professional Development Study (SIM PD Study). American Institutes of Research. https://www.air.org/project/simulation-instruction-mathematics-study-sim-study

Walqui, A., & Bunch, G. C. (Eds.). (2019). Amplifying the curriculum: Designing quality learning opportunities for English learners. Teachers College Press.