Course(s): ENG 101, ENG 102, ENG 102 Honors, and ENG 301/509

Department: English

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor(s): Melanie Gagich, PhD

Syllabus (submitted as PDF): ENG 101, ENG 102 Honors, ENG 102 Hybrid

Number & Level of Students Enrolled:

- ENG 101 (Fall 2020): 38 total students

- ENG 102 (Fall and Spring): 115 total students

- ENG 102 Honors (Fall 2020): 9 students

- ENG 301/509 (Spring 2021): 6 students

Digital Tools/Technologies Used:

- Google Docs

- Blackboard

- Flipgrid

- Jamboard

Author Bio (50-100 words): Melanie Gagich earned her doctorate in Composition and Applied Linguistics from Indiana University of Pennsylvania in 2020 and has been teaching college writing since 2009. She has published her work in the Interactive Journal of Technology and Pedagogy and Writing Spaces. Her research interests include multimodal composition, digital literacy, and open access pedagogy. She served as convener of the DigitalCSU working group from 2018-2020 and as a faculty champion during the 2020-2021 academic year. She also won the inaugural Textbook Hero award with her co-author, Emilie Zickel, for the open access textbook, A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing.

In spring 2020, college writing teachers across the US quickly transitioned their classes from face-to-face to online delivery. As an Associate College Lecturer in the First-Year Writing Program at Cleveland State University, I was no exception. Last spring I wrote a case study, “Reflecting on the Use of the Community of Inquiry Framework to Engage First-Year Writing Students Remotely,” for the Cleveland Teaching Collaborative explaining how I used the Community of Inquiry Framework (Garrison, Anderson, Archer, 2000), to help me quickly transition my courses. However, in the summer of 2020, I had more time to consider how I wanted to approach my classes. In response to a variety of delivery formats I taught in the 2020-2021 academic year (see Table 1), I decided to implement a blended learning delivery approach.

| Semester / Course | Meeting Days / Modes of Delivery |

| Fall 2020 / ENG 101 (two sections) | Mondays and Wednesdays (synchronous Zoom) Fridays (asynchronous) |

| Fall 2020 / ENG 102 (one section) | Tuesdays (synchronous Zoom) Thursdays (asynchronous) |

| Fall 2020 / ENG 102 Honors (one section) | Mondays and Wednesdays (face-to-face on campus) Fridays (asynchronous) |

| Spring 2021 / ENG 102 (two sections) | Mondays (synchronous Zoom) Wednesdays (face-to-face on campus) Friday (asynchronous) |

| Spring 2021 / ENG 102 (one section) | Fully online and asynchronous |

| Spring 2021 / ENG 301/509 (one section) | Mondays and Wednesdays (face-to-face on campus Fridays (asynchronous) |

According to Senar (2015), there are two types of blended learning environments: “Online activity is mixed with classroom meetings…” and “[m]ost course activity is done online, but there are some required face-to-face instructional activities, such as lectures, discussions, labs, or other in-person learning activities.” My courses aligned with the first definition in that students were still required to attend face-to-face and/or synchronous Zoom sessions (depending on the semesters) while also completing work asynchronously. I also chose to apply a blended learning approach because it promotes the three presences of the Community of Inquiry Framework (teaching, social, and cognitive) (Allen, Seaman, & Garrett, 2007; Senar, 2015) and provides space for “learning-centered strategies…through its sustained blend of active, synchronous activities and reflective, independent activities” (Hilliard & Stewart, 2019, “Blended Communities of Inquiry”, para. 1). In light of these benefits, I determined that blended learning delivery was an effective choice; however, I also recognized the need to integrate digital tools to promote success in this learning environment.

Due to the complexity of each semester’s mode of delivery, I understood that I needed to thoughtfully and carefully choose digital tools that would support the blended learning format as well as engage students. Because some classes had face-to-face components while others did not, I wanted to be sure that the digital tools I chose could easily transfer into different spaces. I used Google Docs and Blackboard to organize each class and, after much experimentation, Flipgrid and Jamboard to engage students in a blended learning environment. This case study reviews the benefits and challenges associated with integrating these tools into virtual and face-to-face classrooms while also providing screenshots showing the tools at work in the classroom.

Using Google Docs and Blackboard to Organize Classes

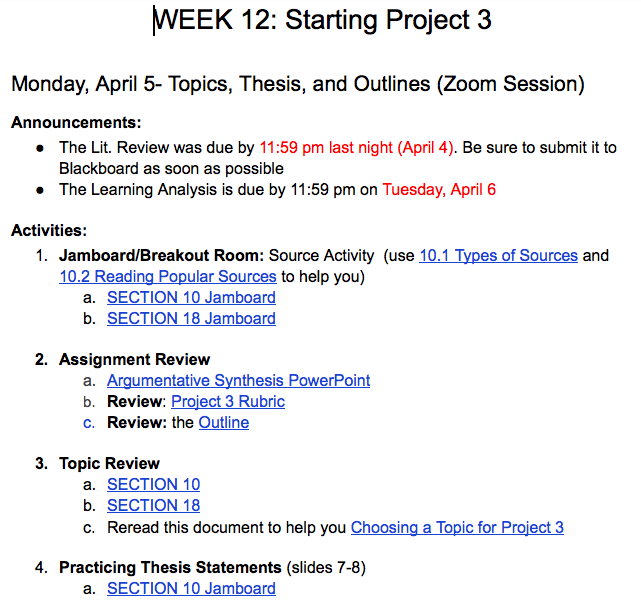

In any learning context, it is important for instructors to organize course materials in order to engage students and promote learning. I used Google Docs and Blackboard to organize all of my classes. Students were given access to a shared Google Doc that contained announcements, synchronous, and asynchronous work (see Figure 1). This format helped students access course work on synchronous days, whether it was held on campus or via Zoom, and directions for completing asynchronous work. The Google Doc maintained the same structure and design throughout the course to help students navigate it. In addition to Google Docs, I also used Blackboard, our learning management system, for students to access the shared course Google Doc, participate in discussion posts, and post assignments. Again, Blackboard was used in a consistent manner and that consistency provided students with structure, no matter the delivery format.

However, while overall the use of these tools helped students navigate the course, find weekly synchronous and asynchronous activities, and complete and post assignments, there were some challenges related to using these digital tools. The most significant challenge was helping students learn how to find and navigate the Google Doc because they needed to access it through Blackboard and use the “outline” feature (or scroll) to find the work for each day. Learning to navigate the Google Doc and use Blackboard to submit work (rather than email it to me) took class time to practice during the first two weeks of class, yet eventually all students in each class were able to successfully manage these organizational tools.

Flipgrid

Flipgrid is “a simple, free, and accessible video discussion experience for learners…”(Flipgrid) and I used it primarily in my fall 2020 ENG 102 Honors course as part of their asynchronous work. For example, students were asked to describe their research process using Flipgrid, share the link on Blackboard, and respond to a peer. Using Blackboard to share the link was somewhat forced because students were easily able to access and respond to videos using the web or phone app. However, I asked students to submit the link via Blackboard because it allowed me to grade their work quickly and easily. So while posting the link was a little clunky for students, I think it worked well as a way to grade their work.

Flipgrid also allowed students to move beyond the traditional written asynchronous Blackboard discussion post and provided them with opportunities to see and connect with each other during the asynchronous Friday sessions. While I had planned to incorporate Flipgrid into all of my courses, due to time constraints and avoiding overloading students with new technologies, I only integrated it into this one class. However, I include it here as a beneficial tool for blended learning due to its potential for more than just a replacement for discussion posts.

In addition to replacing written discussion posts, Flipgrid can be used in a face-to-face or online classroom in a variety of ways. For instance, during peer response workshops, Flipgrid offers students the opportunity to give their classmate real-time feedback, or a student can send a link to their essay to a peer and use Flipgrid to ask questions about their draft, rather than responding in writing. Flipgrid also offers a way for students to engage in active learning practices such as working in pairs or groups. For example, I envision creating a future assignment that asks them to visit various spaces on campus (e.g., the library or student center) as a way to get to know the university. This type of activity would also them to record their experience and easily share it with the class for feedback.

Although Flipgrid is a useful tool, it requires instructors to become comfortable with the technology in order to smoothly integrate it and develop a way to evaluate students’ work. Further, if integrating it into a face-to-face classroom, an instructor may need to navigate COVID-19 restrictions, which means students cannot work closely in groups. Yet, I envision a scenario where students can use this free video creator to conduct peer responses, create introductory videos, interview people on campus, and/or record their experience navigating campus and non-campus spaces.

Jamboard

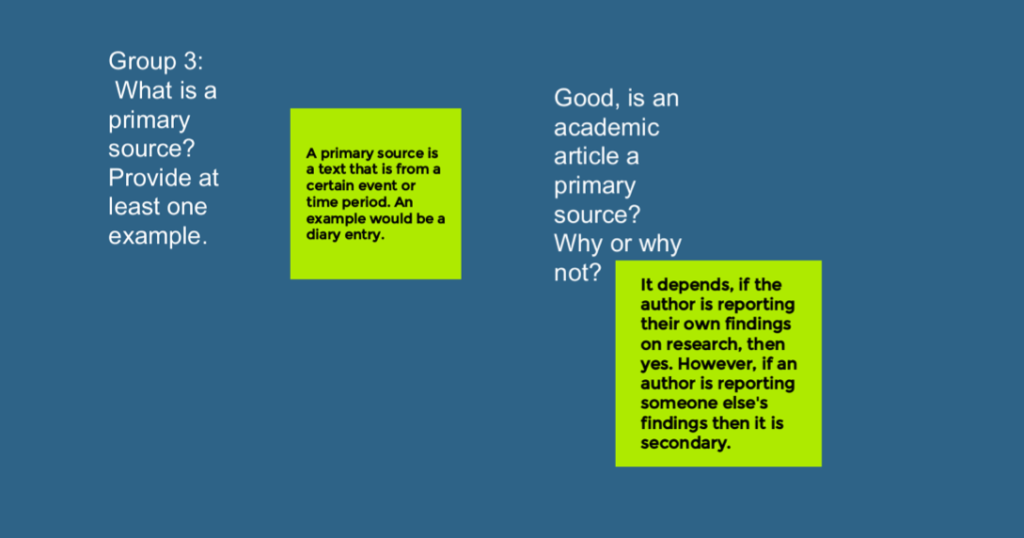

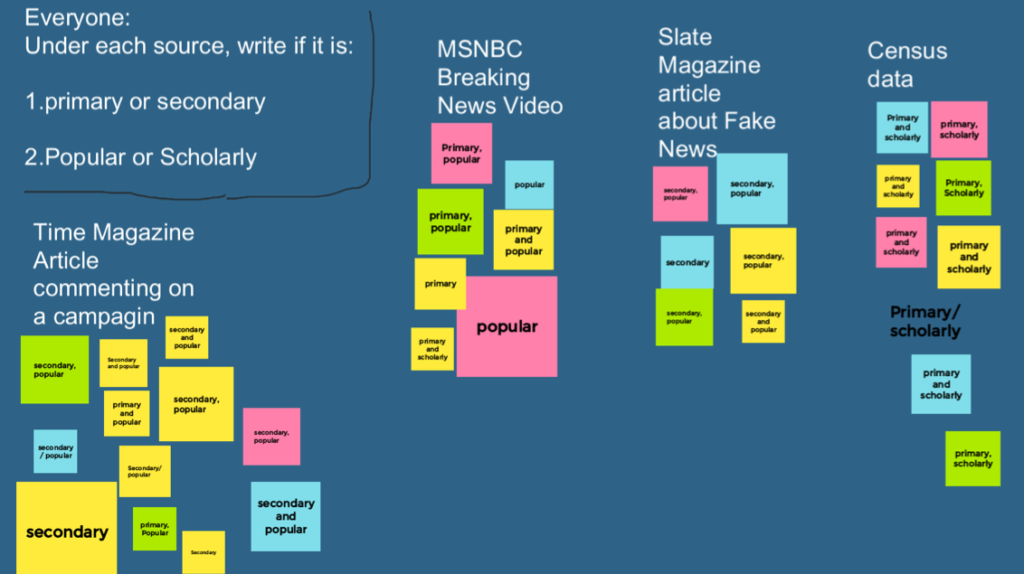

Although I only used Flipgrid in any significant way in one of my classes, I utilized the benefits of an anonymous whiteboard app, Jamboard, in all of my classes over the course of the academic year 2020-2021. Jamboard is a free app from Google that allows students to post anonymous sticky-notes and texts to a whiteboard. In addition to notes and text, students can also copy and paste memes or gifs to the board (see Figure 2). While this may seem basic, the tool complimented many practices I would originally have completed using paper and/or Google Docs such as anonymous question/answer, jigsaw, and comprehension-check activities. Further, I was able to seamlessly integrate Jamboard into my digital framework and class Google Docs. However, I did not use it in tandem with Blackboard because Jamboard served primarily as a space for anonymous responses and to engage students through various active learning practices. As such, I did not need a space on Blackboard to grade students’ work.

The anonymity of Jamboard was especially useful for activities where students would ask questions about an upcoming assignment and/or how they were feeling about it (see Figure 2). Not only were students able to ask their questions but they could see everyone’s answers. This was also especially useful in my fully asynchronous online class where students never met each other. Fully asynchronous students were asked to participate in weekly Jamboards where they would ask questions and I would answer them. However, while I would argue that the anonymity prompted students to participate, it is also impossible to give credit to students who are participating. This was a challenge in the fully asynchronous course because as the semester moved forward, fewer students were participating in the Jamboard. In the future, for an asynchronous course, I would ask students to submit the question as part of their Discussion prompt before sharing it anonymously with their classmates.

Jamboard activities also worked well in face-to-face classrooms. I provided Jamboards asking students to share their questions and feelings about assignments. Although instead of Jigsaw activities, I would ask that students participate individually in the face-to-face classroom setting and answer a set of questions (see Figure 4). While this was not quite as engaging as the group online Jigsaw activity, it allowed students to stay six-feet apart while still helping them engage in class work and provided a basis for whole group discussion.

Concluding Thoughts

As many high schools and colleges across the country begin moving back into classrooms for fall 2021, I am considering how to successfully draw from my experiences with blended learning and incorporate digital tools into my face-to-face and hybrid classes. I will continue to use Google Docs and Blackboard to organize my classes while also integrating Jamboard as a way for individual and, if possible, group learning activities. I also plan to utilize Flipgrid in a way that moves beyond replacing written discussion posts and offer digital peer response and hands-on research opportunities. The challenges moving forward will be to make sure that each digital tool is used purposefully and effectively, rather than choosing a digital tool because it is new or “cool.” Based on my observations from the 2020-2021 academic year, using a blended learning approach is effective and while students will likely be back in classrooms next fall, using technology and digital tools to mediate learning aligns with a blended learning approach.

References

Allen, E. I., Seaman, J., & Garrett, R. (2007). Blending in: The extent and promise of blended education in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.bayviewanalytics.com/reports/blending-in.pdf

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Hilliard, P. L & Stewart, K. M. (2019). Time well spent: Creating a community of inquiry in blended first-year writing courses. The Internet and Higher Education, 41, p. 11-24. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096751618300836?casa_token=h5wSi2LOfPYAAAAA:bUt8bLlKA6-4jQkOvmvV-5YSyNSht4XYLEOYs2l9OtHMowH86f84BHmYWLOO64wM74reGYq5zw#bb0270.

Sener, J. (2015). Updated e-learning definitions. Online Learning Consortium. Retrieved from https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions-2/