Course: ENG 102 College Writing II

Department: English

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Dr. Melanie Gagich

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: Two sections / 48 students

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Blackboard and GoogleDocs

Author Bio: Melanie Gagich earned her doctorate in Composition and Applied Linguistics from Indiana University of Pennsylvania in June 2020 and has been teaching college writing since 2009. She has published her work in the Interactive Journal of Technology and Pedagogy and Writing Spaces. Her research interests include multimodal composition, digital literacy, and open access pedagogy. She served as convener of the DigitalCSU working group from 2018-2020.

Reflecting on the use of the Community of Inquiry Framework to Engage First-Year Writing Students Remotely

I am a First-Year Writing instructor at Cleveland State University and at the beginning of the spring 2020 semester, I prepared my two ENG 102: College Writing II students for a technology-mediated classroom experience (see the syllabus here). According to Garrison (2016), “The most common adoption of online learning in campus-based institutions is blending online and face-to-face experience that increase student engagement” (p. 45). I chose to embrace a blended-learning environment to promote digital literacy skills as well as to help prepare students for careers that have come to rely more and more on technology. Little did I know that the choice to mediate my face-to-face course with technology would prove to be very beneficial once all face-to-face college classes were converted to online classes in March 2020.

ENG 102 is the last in a sequence of writing classes and, in general, focuses on teaching students research literacy skills and source-based research writing. My specific course asked students to complete three major writing projects, in-class activities related to each project, and academic reading/researching. I also required students to have access to laptops during class and students who did not own, or want to use, their own personal laptop were able to rent one for free from CSU’s Mobile Campus. I used Blackboard, the learning management software (LMS) at my institution, and Google Docs in tandem to create an active classroom space where students completed daily writing activities in their personal Google Drive and posted their links to Blackboard for assessment. To establish this design, I provided a workshop on the second day of class to help students learn to navigate both Blackboard and Google Docs. In March 2020, my students were already familiar with using these platforms, had completed one major project (out of three) and were well into their second writing project when the COVID-19 pandemic forced colleges to transition from face-to-face to online instruction.

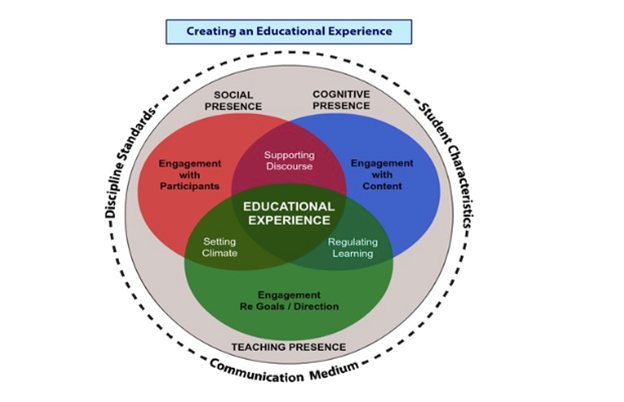

I felt I had a responsibility to construct an online learning environment that not only allowed students to reach course objectives and complete projects but also offered a social and authentic first-year experience during the COVID-19 pandemic online conversion. To do so, I integrated the Community of Inquiry Framework (CoI), an effective model in e-learning, which establishes a structure to promote online learning in the form of three presences: teaching, cognitive, and social (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). The framework (see Figure 1) fosters a collaborative learning environment where community members (i.e., students and the teacher) work together to construct and confirm understanding of course concepts.

I argue that using the CoI framework offered a structured way to develop an effective online learning environment and it helped me convert my course quickly. The framework also guided my pedagogical decisions related to providing a social and learning experience during a time of crisis. While I contend that the CoI framework is an effective heuristic, some students struggled with the additional workload required in this approach to online learning and without the face-to-face experience. In the sub-sections below, I describe each presence, discuss how various assignments I integrated into the curriculum sought to promote that presence, and reflect on how each presence could be fostered more effectively in future iterations of the course.

The Teaching Presence

The teaching presence requires three activities “design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social presences” (Garrison, 2016, p. 61). While the teaching presence is supported by the teacher, it does not imply that the teaching is only completed by the teacher. Ideally, if a course is designed in an optimal way to embrace this presence and promote the cognitive and social presences, then students will begin to see themselves as contributors who have expertise, experience, and feedback to give thus creating an engaged learning environment. Although my teacher-ly presence was obvious in my incremental assessment, informal formative feedback, and “lurking” in some group discussions, the design of the Google Doc encouraged students to enact the teaching presence.

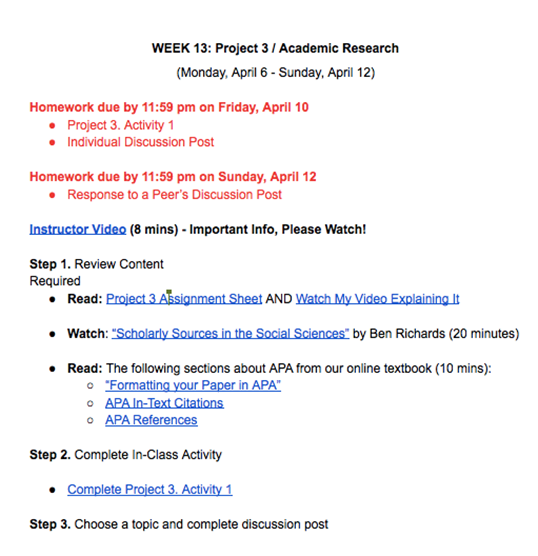

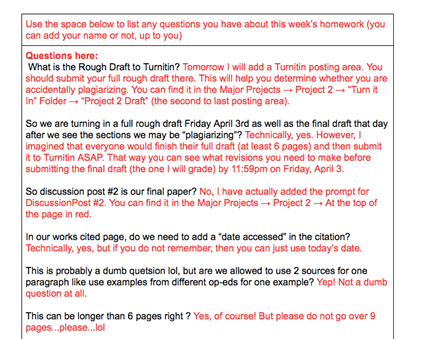

I used a shared course Google Doc (see Figure 2) to facilitate learning and structure the course. The document was updated daily and although I used this tool from the first day of class, when I moved into an online learning space, I revised the structure of the document. I wanted to make the document easy to read and follow, so I used the same structure each week. For example, homework was in red text and I always included “Step 1: Review Content”, “Step 2: Complete In-Class Activity”, “Step 3: Discussion Post”, and an additional space where students could ask questions (see Figure 3). This approach reflects the teaching presence because I facilitated students learning via the GoogleDoc; however, a lot of learning responsibility was placed on the student, which some students reacted to negatively. Warner (2016) notes that sometimes students just want to be told the “right” answer by the instructor and that some students balk against this type of vigorous learning. When implementing such a design in my future online courses, I plan to explain to students in the syllabus the additional workload related to this design in an attempt to respond to this constraint.

The Cognitive Presence

The cognitive presence is the “thinking” element of the CoI framework and while it includes four categories, it is operationalized through a recursive Practical Inquiry (PI) model. The first dimension of PI combines the “psychological (private) and sociological (shared) components of inquiry” and the second “reflects that aspect of inquiry that occurs at the cusp of reflective and shared worlds” (Garrison, p. 60). The first dimension aligns with “triggering events” and “exploration” while the second includes “integration” and “resolution”; however, it is important to not view these categories as static because the cognitive presence reflects a recursive learning process (Garrison, p. 63).

I used various approaches to foster the cognitive presence including small-stake and major assignments. For example, I incorporated weekly in-class writing activities and discussion boards to check understanding of course concepts, foster social interaction, and provide a space for informal feedback from myself. Major writing projects were used from the onset to help students learn course concepts and represented the cognitive presence. When the online conversion transpired, students had completed their first major project and nearly completed their second (a six- to eight-page argumentative essay). Thus, for the second project I maintained my original approach to it: students submitted a rough draft to me for feedback, conducted a digital peer response workshop, and turned-in their work for final feedback.

However, the last project was changed from a twelve- to fifteen-page academic research proposal to three smaller components: a methodology review, a literature review, and a learning reflection. Shifting my expectations for the final project allowed me to help students navigate difficult concepts that they had not experienced before such as APA documentation style, differentiating between methodological approaches to research (e.g. quantitative and qualitative methodologies), and reading long and difficult academic research. Instead of focusing on one cohesive text, breaking the project into three components helped students understand these concepts and focused their attention on learning these research skills versus writing a long cohesive essay. This approach reflected the cognitive presence in that each of the four categories above were enacted within the project.

The Social Presence

It is important to foster social presence at the beginning of a course so that learners can become comfortable in their CoIs, which helps them shift to the cognitive presence (Cooper & Striven, 2017; Garrison, 2016). Open communication, group cohesion, and opportunities to share personal experiences and/or affective responses are the three categories that help form the social presence (Garrison, 2016). However, at the beginning of the semester, the social presence was enacted face-to-face most often in small groups. Moving to a strictly online space made it more difficult for students to form group cohesion, which helps students become more comfortable within their collaborative environment, fosters trust among the group, and promotes the sharing of experiences and emotions. Yet, I added a question space to the shared course Google Doc so students could ask questions anonymously and receive a response from either myself or a classmate (see Figure 3). In one reflection describing their online learning, a student explained that this practice made it easier for them to stay connected to the class because a new question space was created weekly making it easier for them to remain up-to-date in the course and feel connected to the teacher and peers.

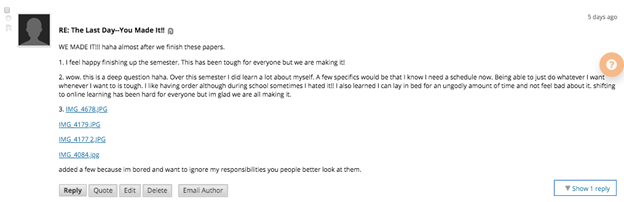

In addition to the Google Doc, I also created an area in Blackboard for students to ask me questions and to communicate with each other (no points were associated with these spaces) but I had no success with this approach to fostering a social presence. Not one student posted in either space. However, I also used the “Discussion” feature on Blackboard where students posted a weekly discussion post that responded to my prompts and in these prompts I asked students to share how they were feeling, a positive experience they had that week, and/or a funny meme, GIF, image, etc. to foster the sharing of emotion and a feeling of togetherness. This approach was moderately successful in that some students (see Figure 4) took that opportunity to reach out to their peers while others were less enthusiastic. To promote the social presence in the future, I will take more care to integrate reflective discussions for students that are not only focused on course content but also provide opportunities to share feelings, experiences, and/or stress-management techniques.

Future Revisions

While I contend that the CoI offered an effective way for me to approach online learning quickly, there are some changes I would make to make online learning more collaborative. Specifically, it is important to consider how to more effectively foster a social presence when students may never meet each other face-to-face. In the context I described here, students had already connected with each for eight weeks before being thrust into an online learning environment, but future iterations of my course might not provide any face-to-face interaction so students will only socialize with each other virtually. As such, I plan to integrate weekly video sharing assignments using Flipgrid (freeware that allows students to create short videos, share them, and respond to peers) so that students can see each other and feel that there is a place to have fun in the digital classroom. In terms of providing a social space devoted to learning course concepts, I will also create an online work area (i.e., break-out rooms on Zoom) where students can meet and where I am only a lurking presence so that they can form some relationships. This type of space will also foster the teaching presence because while I will facilitate the learning by creating the environment, students will be required to participate in active learning guided by themselves and their peers.

It is important to note that embracing CoI to design an online course does not mean simply adding discussion boards or forced response forums that serve as mandatory “check-ins.” Although it is tempting to rely on efficiency and convenience associated with this type of assignment, due to time constraints associated with creating and facilitating the curriculum (Warner, 2016), they may not promote a collaborative learning environment, even though they are convenient ways to offer students feedback. However, if an instructor is interested in using the CoI framework to create a shared and collaborative learning space, then using simple tools such as Google Docs and Blackboard can make that possible, no matter the learning environment.

References

Cooper, T. & Scriven, R. (2017). Communities of inquiry in curriculum approach to online learning: Strengths and limitations in context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(4), 22-37. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3026

Garrison, R. D. (2016). Thinking collaboratively: Learning in a Community of Inquiry. New York: Routledge.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Warner, A. G. (2016). Developing a community of inquiry in a face-to-face class: How an online learning framework can enrich traditional classroom practice. Journal of Management Education, 40(4), 1-21. doi:10.1177/1052562916629515

3 thoughts on “Reflecting on the use of the Community of Inquiry Framework to Engage First-Year Writing Students Remotely”