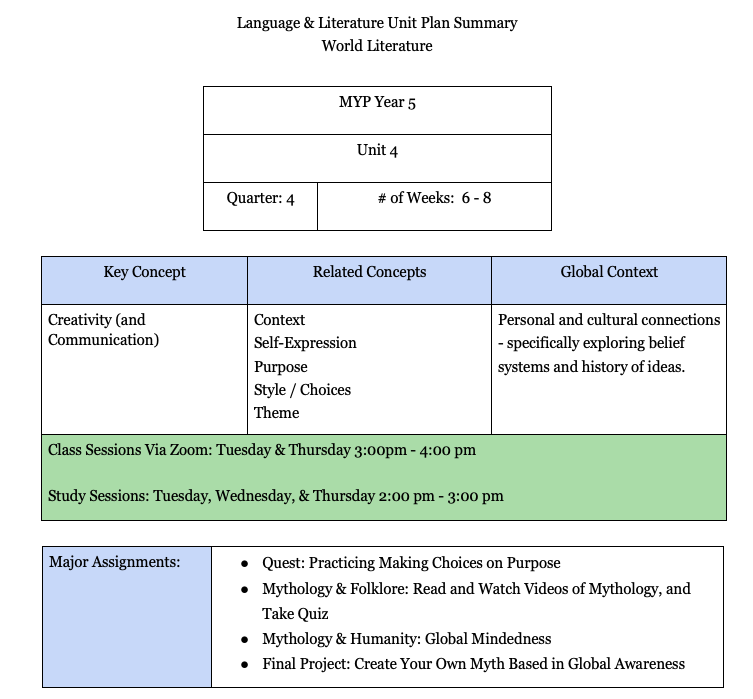

Course(s): World Literature

Department: Language & Literature

Institution: Campus International High School

Instructor(s): Sophia Higginbottom

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: 92 Tenth grade students

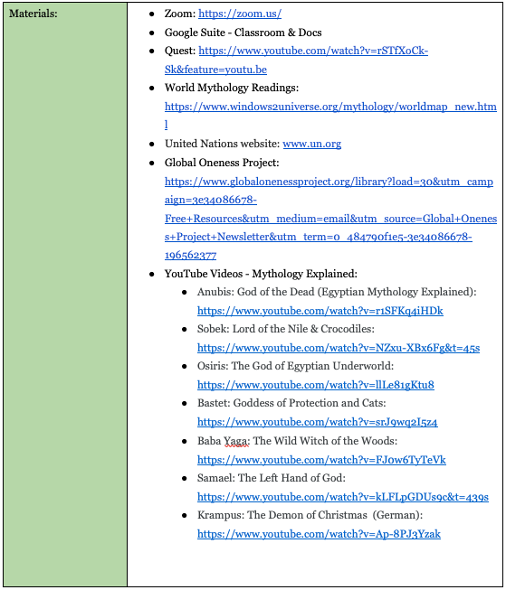

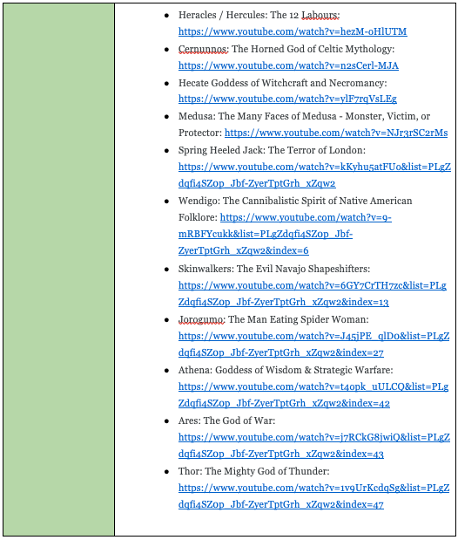

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Google Classroom, Zoom, YouTube, Global Oneness Project, CommonLit, UN.org

Author Bio:

With a background in International Studies, the Arts, and nonprofit sector work, Sophia Higginbottom brings real world experience and vision into classrooms where young people learn to deeply respect and embrace cultural differences while creating change in their communities. Higginbottom was born and raised in Cleveland, OH and graduated from Cleveland public school. She holds a degree in Liberal Arts from Cuyahoga Community College and a degree in International Studies from Denison University. She has previously served as a City Year Corps Member at East Technical High School, a Teach For America educator, an Intervention Specialist at Davis Aerospace and Maritime High School, and a World Literature instructor at Campus International High School.

Simultaneously Stimulating Autonomy and Global Citizenship: A Case Study on Education Through the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the spring of 2020, all educational courses were to be concluded via online resources due to the coronavirus pandemic. This case-study follows the changes made to accommodate new COVID-19 restrictions for our community and the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD), while continuing to foster autonomy and global citizenship in a tenth grade World Literature course, originally focused on bringing various aspects of world cultures into the study and creation of literature.

Before COVID-19

At the start of the course, various methods of knowledge distribution were introduced including Google Classroom, CommonLit, various novels, articles, poetry texts and online collections. A thorough introduction to these resources at the start of the course was a saving grace when considering the unexpected transition to online learning. Though there was much integration of technology use in the classroom setting, students still found themselves unprepared in many ways for the full time switch to technology. Prior to the transition, students had a working knowledge of viewing and submitting work through the Google Classroom platform. Students were regularly required to complete online research, type essays, create videos, and submit content via online platforms. In-class tutorials were given using SmartBoard technology and guided practice to ensure proper and easy classroom usage of technology and online resources.

These methods and in-classroom learning environments created their own methods of developing autonomy within students. These included lunch time office hours which students could choose to sign up for, various forms of in-person interaction which allowed opportunities for students to ask for help in an immediate context, and most importantly, accountability for work, especially within the online platform, whether in class or absent.

As a continuation of the stimulation of autonomy within students, this year-long Language & Literaturecourse also focused on developing global awareness and citizenship within them. Working with content from Oceania, Latin America, Africa, and other places, began to develop global awareness. Students’ broadened their personal horizons through not only their experiences with literary analysis, research writing, and poetry, but also with exposure to novels from regions previously unknown to them, multi-lingual spoken word, works in translation, and non-literary texts of revolutions from around the globe.

Transitioning to Online Learning

In transitioning to fully online learning environments, the methods of knowledge distribution changed substantially. The first necessity was to ask students to complete a survey, which was posted into their Google Classrooms and sent via email to everyone enrolled in the course. This survey asked questions such as whether or not students had access to the internet, computers, or cell phones regularly. It asked what would be the best time of day for live virtual class sessions, study sessions, and office hours. Finally, the survey also asked students to describe and select the ways they believed they could best learn in this new distance-learning world. At the conclusion of the survey, 71 of the 92 students in the class completed the survey. The results allowed classes to be scheduled for times where the most participation was available; in this case that was holding classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays for an hour each session, and holding office hours and study sessions on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. The surveys also allowed for consideration of how assignments were being completed, so as not to ask too much of students who may have limited internet access, only a cell phone to work from, competing priorities, etc. In the case of this class, one to two assignments were to be completed each week. These assignments were posted at least two weeks prior to their due dates to allow ample time for students to complete them or reach out for assistance in some fashion.

There were so many resources presented at the start of the closings, and sifting through them to find practical and user-friendly platforms took quite a bit of time. As previously stated, student familiarity with the Google Classroom platform helped quite a bit with transitioning to fully online learning. Students received notifications to their emails each time there was a new message or assignment posted into Google Classroom, letting them know to check our classroom site. Within both email and Google Classroom, students could comment for clarification, send messages for help or get assistance with any other needs from peers and instructors, including Intervention Specialists, to keep them connected to their support systems. Through the use of technological devices (i.e. laptops and iPads – many of which were provided by the Cleveland Metropolitan School District – and parent or student cell phones) and resources at our disposal (i.e. YouTube, Zoom, Google Suites, etc.), students and families were able to remain supported by teachers. This was also a huge opportunity for growth in teaching when it came to incorporating things students enjoyed and wanted to learn about more into the curriculum. Finding ways to balance work that continued to challenge and stimulate growth, while driving students to become global citizens, and develop and support personal opinions.

Zoom was the next tool explored. All live virtual sessions, office hours, and study sessions were completed using Zoom. At the time when classes resumed, I set up recurring Zoom sessions for each type of meeting. The codes and passwords for entry into all sessions were then posted into the Google Classroom for students and families to access. I also worked with many students and families to walk through the steps of accessing our Zoom sessions together (via phone calls mainly) so that they could access sessions on their own. The main class sessions were also recorded and posted into the Google Classroom after each meeting, along with the presentations, so that even students who had competing time commitments could go back to view the previous sessions and discussions whenever convenient for them. Students were empowered to take initiative and control their own learning during this time in a more profound way than ever before. These platforms, despite instructors initiating many connections to students, places much of the onus on the students to ask for help, connect, and participate in sessions. Though much different than the traditional “high school model” of teaching, students who participated developed a stronger sense of independence, preparing them more for the technology and resources used in colleges and universities.

As we moved forward in the semester, our content became more focused on analysis of global issues and finding creative solutions to aid change. Using many different platforms, including GlobalOnenessProject, CommonLit, the United Nations website and various YouTube channels on mythology and folklore, students were able to witness global issues, view the perspectives of people experiencing those issues, witness changes being put into action by global and local organizations, choose a global issue which sparked their passion, and create their own stories to create an impact through their creativity. Especially for this final piece of learning for the year, students had to have a mandatory one on one conference, via email or Zoom, to talk through their ideas thoroughly. This stimulation of deep thought alongside creative outlets produced outcomes including student–facilitated Zoom sessions about global issues, as well as student-created videos, slideshows, and written stories about world issues which students felt connected to, even from afar.

In reflecting on the semester, I would hope to encourage more participation, though I understand the fact of many students simply not having access to technology or internet services, or having competing priorities in such an unprecedented time. Both Zoom and Google Classroom proved to be immensely helpful platforms for learning. Despite hindering factors, the goal is always to have participation from all students, so that we may aid in their development as citizens of our world.

Language & Literature Unit Plan Summary World Literature