Course(s): Data Visualization and Information Design, Corporate Identity, Graphic Design for Social and Cultural Contexts

Department: Art and Design

Institution: Cleveland State University

Instructor: Sarah Rutherford

Number & Level of Students Enrolled: 300/400 level, 20 students on average

Digital Tools/Technologies Used: Miro

Author Bio: Sarah Rutherford is an Associate Professor of Design at Cleveland State University who researches, writes, and speaks about pedagogy and learning in higher education. She holds an M.F.A. from the School of Visual Communication Design at Kent State University. A Missouri native, Sarah earned a B.F.A in Visual Communications and a B.A. in English from Truman State University.

Introduction

In the spring of 2022, I integrated ungrading into my classrooms with the aim of giving students more control over their workload and how they engaged with material. This case study documents four semesters using the ungrading process. In addition to providing resources and materials, I share recommendations and student reactions to participating in a “gradeless” classroom.

Since students returned to campus in fall 2021 after emergency remote teaching (ERT), classroom engagement has been a widespread issue in higher education regardless of institution type, classroom size, or discipline (McMurtrie, 2022).

ERT showed us in real time, particularly at institutions like Cleveland State University, how inequities affected our students’ ability to engage and learn. It also revealed the ineffectiveness of many of the typical hallmarks of the higher ed classroom like long lectures, high stakes testing, and inflexible policies. Seeking solutions, I began an exploration of equitable and anti-racist teaching methods, which led me to critical pedagogy theory. Critical pedagogy creates a framework for instructors to reflect on their relationship to structural power and its ties to the values of white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism, and paternalism (Brookfield, 2017). I looked at my teaching, the inherited models and policies of design education that showed up in my classes (many of which were the same as what I experienced as an undergrad, 20 years ago and several states away) and the most significant concerns among my students. Autonomy and intrinsic motivation are two characteristics that predict successful learning for college students. I kept an eye out for policies or approaches that enabled students to rely on me rather than themselves.

Through critical reflection, I saw how the power I upheld was working against my goals for students and how it centered on inherited structures I was trying to eradicate in my classroom. I also realized that as an instructor, I controlled many of the factors that lead students to rely on extrinsic motivation. I recognized that a classroom that centralizes the instructor’s policies and decisions impedes student agency. When a classroom is instructor-centered, students might feel that they have as little control over their learning or motivation as they do over assignments or policies. In order to make my classroom student-centered I needed to look at how I held and used my power in the classroom.

The primary way I’ve restructured my teaching to share power with students is by integrating ungrading into my classes. I started in the spring of 2022 with the aim of giving students more control over their workload and how they engaged with material. The method was so successful, I’ve adopted it in every class since. If ungrading is a new or challenging concept, keep this in mind: grades do not track or demonstrate learning, they measure performance (Kohn, 2013). Sometimes grades and learning correlate. But one is not a guarantee of the other.

Why Did I Want to Make the Change to Ungrading?

- I was exploring challenging traditional classroom power models.

- ERT changed how I work with students.

- I was observing student disengagement in and out of class.

- There were lots of absences in my classes.

- I observed very stressed students.

- I wanted to promote student autonomy.

- I wanted to create an environment that emphasized intrinsic motivation.

I teach Design, which is almost universally based on a subjective grading system. Students primarily complete project-based work that lasts several weeks. Grades are assigned based on an instructor’s evaluation of the quality of the finished product and their observation of a student’s engagement in the process. A-quality work from a student who has not participated in class critiques or showed progress will typically not result in an A grade. While the emphasis is on process, an instructor’s subjective assessment is still a large component of the grade, resulting in a great deal of power in their hands.

In addition to disengagement and frequent absences, I was observing greater levels of stress and poor mental health among my students. The problem had grown to the point it was a constant topic of conversation among my Design colleagues. I needed a solution that would not only reduce stress, but also address disengagement by encouraging students to have more agency over their learning decisions. My solution was to adopt a contract grading system. Students would contract for a final grade in the course based on how much work they would like to (or were able to) complete.

What Were My Goals?

- Contribute to a student-centered classroom.

- Emphasize learning over performance.

- Address attendance issues and disengagement.

- Promote equity.

- Empower students to make their own decisions about their effort and workload.

- Remove consequences for risk taking and failure.

When introducing the contract grading system, I first talked with students about identifying what they wanted out of the class and then how to consider those goals with what they would be able to accomplish. Some students wanted an A no matter what because getting As was a part of their identity. Others saw an opportunity to go for a grade that might typically be out of their reach. Some recognized that their capacity for coursework was compromised by a job or other commitments. And still others saw a means to reduce pressure and better manage their mental health.

In the Design program, students create a portfolio of visual work that is the primary instrument by which they are hired after graduation. A student’s portfolio showcases their creative and technical ability and is made up of projects from most of their major courses. I framed work in class as something to do for themselves, for the value of learning and building a great portfolio.

No matter the motivation for their decision, students got to make the best choice for themselves. They could also pursue whatever creative solutions they wanted without worrying that it might affect their grade.

How Does My Contract Grading Model Work?

- Students contract for a grade based on workload that I set.

- Everyone does the same amount of “base” work.

- Courses include self-assessments.

- I emphasize in-class feedback to promote attendance and participation.

- Students assign their own midterm grades based on self-assessment.

- Work is peer evaluated to a standard of satisfactory/unsatisfactory.

- Students set the standards for peer evaluation.

- I do not penalize late assignments.

I relied heavily on the book Ungrading to develop my contract grading system (other resources are linked at the end of this essay). Students contract for an A, B, or C grade in the class based on the amount of work they wish to complete. I set the workloads associated with each grade based on point rubrics from my old subjective grading method. Nearly all work in my classes is project-based, so workload variance is based on lower grade contracts having fewer associated deliverables. Because there is content I want everyone to experience, all students do the same “base” workload (see below grade contract for full language).

Students do not receive project grades, only a midterm grade and final grade. I eliminated the subjective component of assessment, providing only formative and summative feedback. Much of this feedback happens in class, so students have another incentive for attending. Students assign their own midterm grade based on a self-assessment of their participation and progress in the course (see below example). Students have the option of adjusting their grade contract at any time.

In order to ensure students meet an acceptable standard based on project workload, final work is peer evaluated to a standard of satisfactory/unsatisfactory. Students who receive a U grade can resubmit as many times as needed. Students set the standards for peer evaluation. I typically do this in class as a verbal discussion and write the results on a white board. Students anonymously review each other’s work based on the agreed-upon standards, usually directly in line with project requirements.

What Happened?

- Students love it.

- I saw improved attendance and participation.

- Students self-selected to change their contracts.

- I made revisions based on student feedback.

Most students were enthusiastic about the system from the moment I introduced it. Students who associated their identity with high grades did have some trouble with the concept at first. After three semesters, I can now rely on students who have experienced contract grading to explain (and evangelize) to the newcomers.

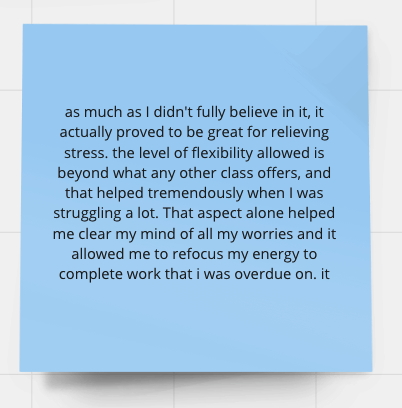

Figure 1: End-of-semester evaluation comment from a student about contract grading.

Figure 2: End-of-semester evaluation comment from a student about contract grading.

At the end of each semester, I facilitate a class evaluation where students first answer written questions on Miro and then have a discussion on the themes they brought up. In these evaluations, I ask “What were your favorite parts of the ungrading approach for this class?” Students repeatedly praise how contract grading reduces pressure, helps them feel less stressed, and gives them more flexibility (see figs. 1 and 2). They’ve noted that they are “truly able to commit to learning,” that they like “not feeling judged on aesthetics but on process,” and that they “feel happy designing and excited to see how things turn out rather than ‘designing for an A.’”

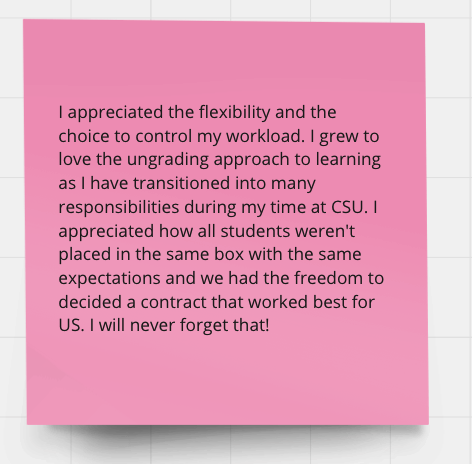

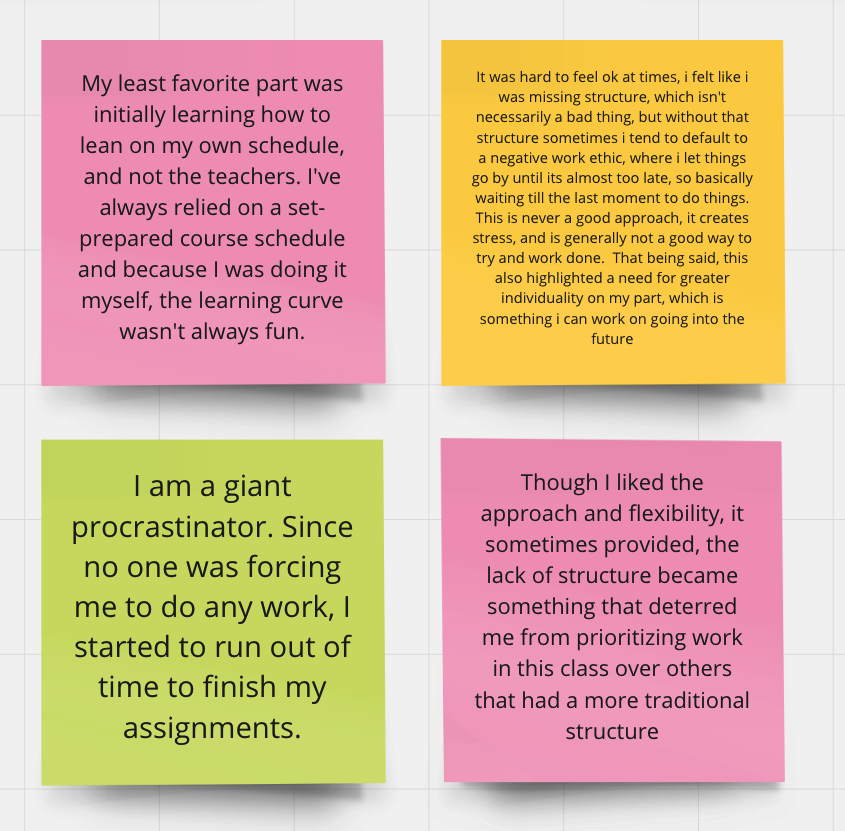

Figure 3: End-of-semester evaluation comments from students about tracking their own schedule.

Figure 4: Students had “no complaints” about contract grading in their end-of-semester evaluation.

I also ask, “What were your least favorite parts of the ungrading approach for this class?” Answers to this question have been the most helpful as I revise the system. In my first iteration of contract grading, students made their own production schedule for the semester, sequencing their contracted assignments as they chose. I learned this was too much flexibility for students. While many students liked it, several others in two different classes expressed how difficult it was for them to maintain momentum and accountability (see fig. 3). I then restructured the contracts and semester calendar so that everyone would work on each assignment at the same time. After I made this change, the most common answer to their “least favorite” part of ungrading was some variation of “no complaints” (see fig. 4).

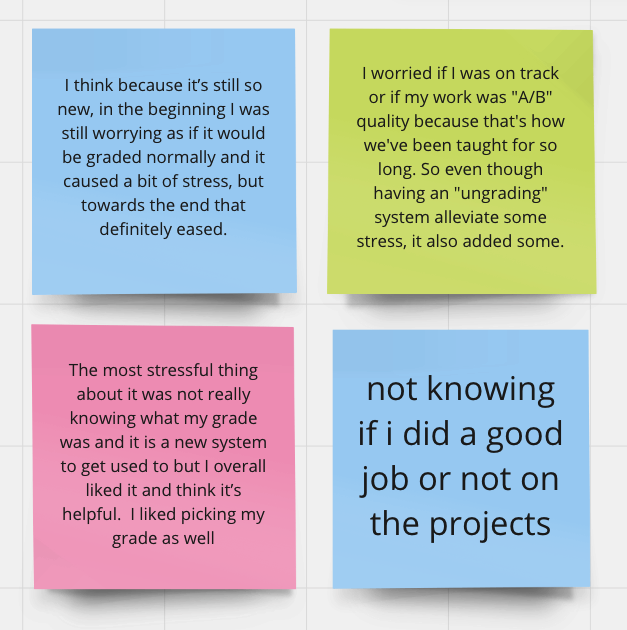

Figure 5: End-of-semester evaluation comments from students about missing progressive grades.

The other most common challenge expressed by students was not knowing where they stood or how well they were doing because they were not receiving grades along the way (see fig. 5). This reveals students’ deep connection to being measured or “paid” with the capital of grades. Students are conditioned to understand how to evaluate their performance (grades from the professor) but not how much or what they have learned. I currently incorporate both small, 1–2 question learning assessments and longer quiz-style self-assessments. In future classes I would like to make learning assessment a more frequent, detailed process to help students understand how to gauge their learning.

Beyond students’ appreciation of the system, I am seeing the results I hoped for when I initially started ungrading. Attendance is robust, students are active and engaged in class, and ungrading opens opportunities to highlight how students might own their actions to better control their success outcomes. While they still experience stress, it’s never about their grade in my class. I see my students learning and the quality of their work has not diminished. I have also been released from the emotional burden of subjective grading. The changes I have seen cannot be solely attributed to contract grading; I also reworked my attendance policy and integrated more in-class assignments and activities. Contract grading has completely shifted my teaching experience. The only challenge for me was the initial effort to set up the system. Like my students, I have “no complaints.”

Sources

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. Jossey-Bass.

Kohn, A. (2013). The Case Against Grades. Counterpoints, 451, 143–153.

McMurtrie, B. (2022). A “Stunning” Level of Student Disconnection. Chronicle of Higher Education, 68(17), 12–12. https://www.chronicle.com/article/a-stunning-level-of-student-disconnection

Resources

- How I Contract Grade by Ryan C. Cordell: https://ryancordell.org/teaching/contract-grading/

- Grade Contract for Technologies of Text taught by Ryan C. Cordell: https://f19tot.ryancordell.org/assignments/

- So Your Instructor is Using Contract Grading… by Dan Melzer, D.J. Quinn, Lisa Sperber, and Sarah Faye: https://writingcommons.org/article/so-your-instructor-is-using-contract-grading/

- I Have Seen the Glories of the Grading Contract… by John Warner: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/just-visiting/i-have-seen-glories-grading-contract

- Grading: Ego, Control, and Varieties of Authority by John Warner: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/just-visiting/grading-ego-control-and-varieties-authority